Introduction

Henry Burt was a master shoemaker at Odcombe and later Hardington Moor. He was married three times and lost his second wife to tuberculosis. His third marriage was particularly eventful because it brought him close to the key figures involved in a sensational murder case.

His life story illustrates how illegitimacy, remarriage and death shaped family relationships and responsibilities.

Childhood at Odcombe

Henry was born at Odcombe in about 1807, the fourth of six sons born to Mark and Jane Burt. His father was a farm labourer. Henry’s mother died in January 1819, aged 36.

Occupation

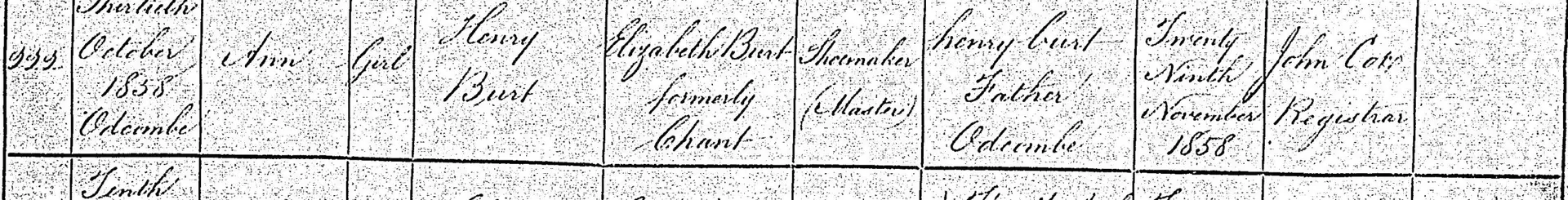

Henry was a boot and shoemaker for most of his adult life. The birth certificate of his daughter Ann confirms that he was in business as a master shoemaker.[1]

First marriage

As a young man, Henry moved to the village of Kingstone, ten miles west of Odcombe, where he met Ann Chick. The couple married at Kingstone on 27 December 1829, both signing the register with a cross. They settled at Higher Odcombe, where Henry worked as a shoemaker. The 1851 census recorded Ann as a glover. Their marriage lasted twenty-six years, but they had no children. Ann died in July or August 1855, aged 54.[2]

Second marriage

On 13 May 1856, Henry married Elizabeth Chant at Odcombe. At the time, Henry was about 49 years old, and Elizabeth was sixteen years younger. By then, he had learned to write his name, and he signed the register “henry burt.” Elizabeth was the daughter of Charles and Sarah Burt of Odcombe. When she was 19, she had an illegitimate daughter, also named Elizabeth. The 1851 census recorded Elizabeth (the unmarried mother) living with her married sister at Sutton Montis while her mother cared for her daughter at Odcombe. After she married Henry, her daughter lived with them and later helped Henry with his shoemaking.

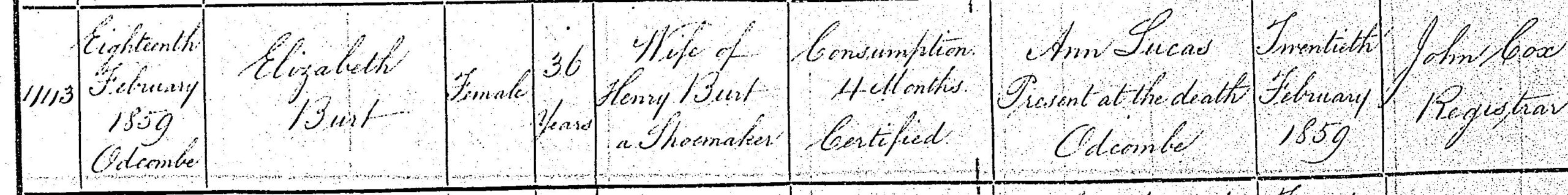

Henry’s second marriage began well, and Elizabeth was soon pregnant. Their daughter, Jane, was born in June or July 1857. Early in the following year, Elizabeth became pregnant again. However, this pregnancy may have sapped her strength as, in September 1858, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Her baby, Ann, was born on 30 October 1858 but died two months later. Elizabeth’s illness progressed rapidly, and she passed away on February 18, 1859, at the young age of 36.

Third marriage

On 28 December 1861, Henry married Elizabeth Hallett at Crewkerne.[3] Elizabeth was the widow of John Hallett, Hardington’s former thatcher, and was about two years younger than Henry. Her youngest child, Jane Lucinda, born in 1850, still lived at home. After the marriage, Elizabeth and Lucinda joined Henry at Odcombe.

Elizabeth was a termagant with a fiery temper. In 1847, she reacted angrily when Peter Hodges, the village schoolmaster, caned her son for misbehaving in church. Upon learning what had happened, she and her husband confronted Hodges in the churchyard, launching an abusive attack as he left the church. While her husband’s attack was only verbal, Elizabeth resorted to physical force, grabbing Hodges by the collar and shaking him. She also directed her anger at the entire congregation, denouncing them as “a congregation of devils.”[4]

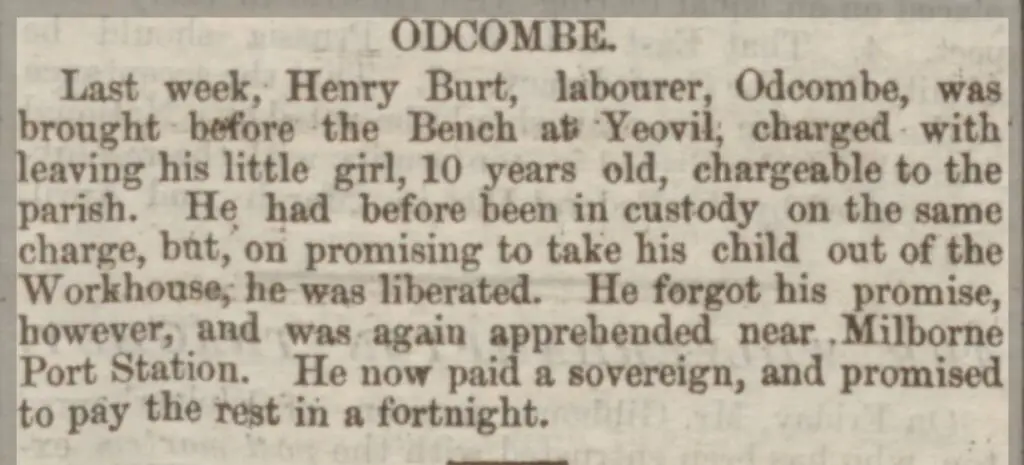

It may have been Elizabeth who was mainly responsible for Henry neglecting his duty to his daughter. In August 1863, he was brought before the Yeovil magistrates accused of leaving his daughter chargeable to the parish. He paid a sovereign and promised to pay the rest in a fortnight.[5] Although the newspapers reported the girl’s age as ten, she was, in fact, six. He promised the magistrates to take her out of the workhouse, and he may have kept his word as by April 1871, she lived with him and her stepmother.

Hardington

By 1864, Henry and his family lived at Hardington.[6]

In December 1865 and March 1866, Henry testified in a court case concerning the theft of some ducks from John Yeandle.

In the early 1860s, Henry’s stepdaughter, Elizabeth Chant, probably entered domestic service at East Coker. On 12 February 1866, she married Lionel Harrison at East Coker. He was a farm labourer who later became a woodsman at Pendomer.

During the 1870s, Lucinda Hallett caused immense upheaval for her mother and Henry. In 1871, she had an illegitimate daughter. Subsequently, she began a relationship with Giles Hutchings, an unruly and violent young man well-known to the police.[7] This relationship quickly led to trouble when, in July 1872, Lucinda was fined 5s for attacking a policeman trying to arrest Giles and his brother, George.[8] Despite this warning of what might follow, she married Giles at Holy Trinity Church, Yeovil, on 10 October 1872.

Four years later, Lucinda and her family became swept up in a sensational murder investigation and manhunt when Giles, along with his father, brother and another man, were suspected of killing PC Nathaniel Cox. After fleeing the scene of the attack, they went into hiding, prompting the police to conduct a prolonged and extensive search, which included the homes of relatives and friends. When they were eventually caught and put on trial, they were found guilty and given long jail sentences, although Giles’s father was subsequently given a free pardon.

After Giles was imprisoned in 1877, Lucinda became a social pariah. She was evicted from her home in October 1878 but refused to go into the workhouse, preferring to live in derelict houses or camp on the side of the road. She served multiple prison sentences for failing to support her children despite being too impoverished to do so. Eventually, her children were taken into care, and she lived with her mother and Henry.

Henry died in 1885, aged 80, and his daughter, Jane, died at about the same time, 29. Elizabeth died in 1887, aged 78, and Lucinda died shortly afterwards.

References

[1] Birth certificate of Ann Burt, 1858.

[2] Ann Burt was buried at Odcombe on 6 August 1855.

[3] Henry Burt signed his name, but Elizabeth put a mark. According to the marriage register, they were both resident in Crewkerne at the time of their marriage.

[4] Sherborne Mercury, 2 October 1847, p.3.

[5] Western Gazette, 29 August 1863, p.4.

[6] Guardian valuations.

[7] It is possible that Giles was the father of Lucinda’s illegitimate daughter, in which case their relationship began in 1870 or earlier.

[8] Western Gazette, 5 July 1872, p.7.