Introduction

Isaac Hawker served as a clergyman at Hardington Mandeville from about August 1907 to March 1909, bringing with him long and varied experience. He had previously been vicar of a poor parish in Plymouth for twenty-seven years and vicar of Ironbridge for nine. Throughout his career, he was a committed evangelical, active in promoting Protestant causes and opposing ritualism within the Church of England. Alongside his parochial work, he took a sustained interest in social issues, serving for many years as a Poor Law Guardian and supporting a wide range of charitable organisations. His energy, diligence, and organisational ability were widely admired, though his uncompromising religious views and readiness to engage in confessional conflict contributed to the bitter controversies of the day.

Childhood

Isaac was born at Trusham rectory on 4 April 1835, the tenth and last child of Thomas Hawker and his second wife, Agnes Watson.[1]

He was born into a clerical family. His grandfather was Rev. Robert Hawker, an evangelical preacher known as “Star of the West” for his popular appeal. His father served as the curate of Trusham from 1818 until his death in 1848, while his uncle, John Hawker, was the vicar of Charles and the minister of Eldad Chapel.[2] His cousin, Rev. Robert Stephen Hawker, was the celebrated poet and parson of Morwenstow, Cornwall.[3]

The family was financially secure. In addition to his clerical income, Thomas Hawker received the interest on £7,200 in 3 per cent consols.[4] It was also a scholarly household, steeped in Protestantism but open to broader intellectual enquiry. Thomas’s library included scientific and reference works, such as the Biographia Britannica and the Universal Dictionary, as well as Puritan theology in the works of Flavel, Charnock, and Hervey, Cruden’s biblical concordance, and nine volumes of his father Robert Hawker’s Poor Man’s Commentary. Thomas also owned a microscope and a telescope.[5]

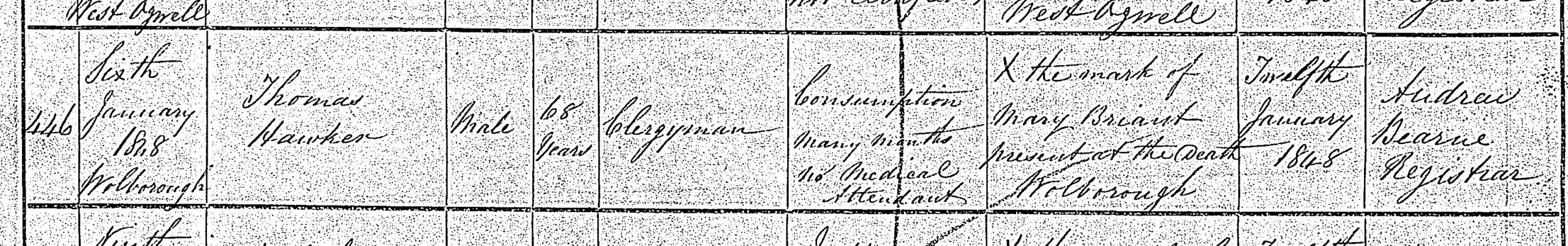

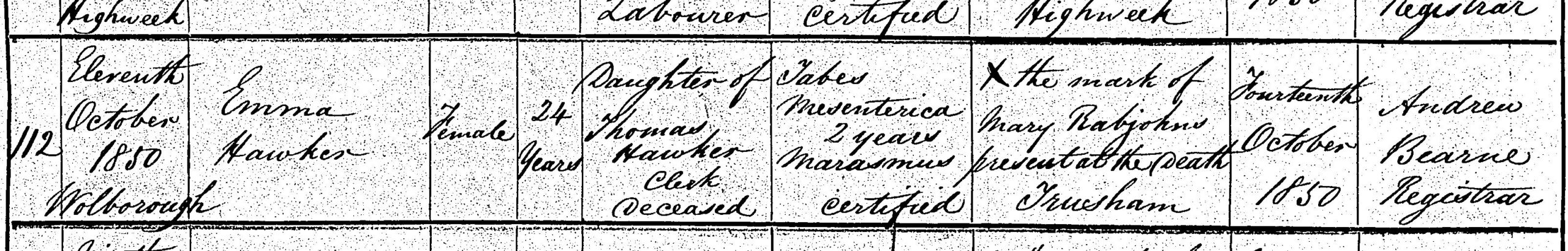

In terms of health, however, the family was far less secure, as the incidence of early deaths in the family was high. By the time of Isaac’s birth, Thomas Hawker had lost not only his first wife, who died at the age of 36, but also six of the nine children of his first marriage and four of his second.[6] Another son by his first marriage died when Isaac was two years old. In 1848, when Isaac was twelve, his father died, followed by the deaths of his sister Emma and half-brother William in 1850, and his brother Stafford in 1851.[7] These latter deaths were attributed to tuberculosis, and it is possible that several of the earlier losses had the same cause. Such repeated bereavements are likely to have had a profound effect on Isaac, particularly within an evangelical culture that emphasised death, judgement, and salvation.

Thomas left specific bequests of books and personal items to each of his surviving children. Isaac was left “all Hervey’s works” and a telescope, along with a legacy of £1,000, to be received after Agnes’s death. “Hervey” refers to Rev. James Hervey (1714–1758), a popular eighteenth-century devotional author whose multi-volume collected works remained standard reading in clerical households throughout the nineteenth century. He had served as a curate at Bideford, and his writings were well known in Devon’s clerical circles.

Following Thomas’s death, Agnes moved with her family to Fore Street, Totnes, where she was supported by the income from the consols.[8] Isaac was educated at Tor School, Montvidere House, Torquay, a boarding school established in 1838 to provide young gentlemen with a classical, mathematical, and commercial education.[9] The 1851 census recorded him as a pupil teacher at the school.[10]

Early career

Isaac followed the family tradition of becoming a clergyman, beginning his training in the north of England. After attending St Aidan’s College, Birkenhead in 1857, he was ordained as a deacon on 25 September 1859 at Durham and licensed to the curacy of Holy Trinity Church, South Shields.[11] He was ordained as a priest at Durham on 24 September 1860.[12]

The first decade of his career was characterised by mobility. After leaving South Shields in 1861, he served at St Stephen’s, Norwich, before moving to Shepton Mallet, where he served under the rector, Rev. Henry Pratt, B.A., in 1862.[13] He then moved to Charles, Plymouth, where he served under the vicar, Rev. Henry Addington Greaves, M.A., from 1863 to 1866.[14] He then moved to Faringdon in Berkshire, where he served under the Devon-born Rev. Henry Barne, M.A., until 1868.[15] It is difficult to determine whether this pattern of movement was driven by missionary zeal, a desire to explore the country or some other motive.

Isaac was a popular figure. When he left Holy Trinity, South Shields, his parishioners presented him with a gold watch and ring.[16] When he left, Faringdon, he was presented with £40 and a scroll.[17]

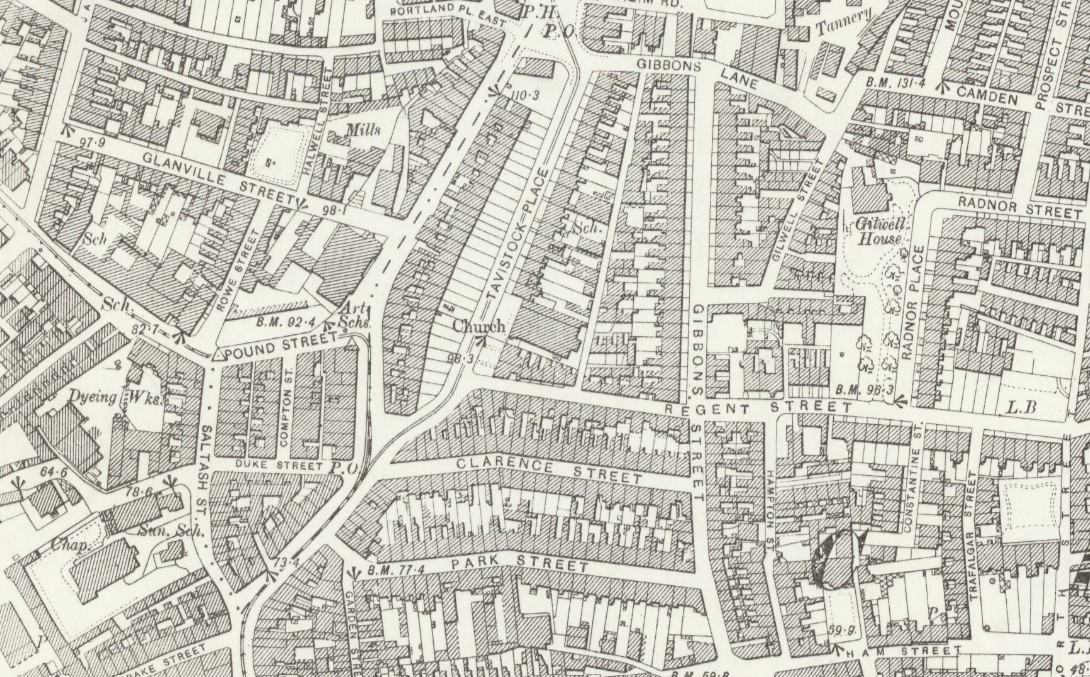

St Saviour’s, Plymouth

In February 1868, the Bishop of Exeter collated him to the sole charge of the district of St Saviour’s, Plymouth, on the nomination of Rev. Francis Barnes, M.A., the vicar of Trinity Church, Plymouth.[18] Barnes had led the effort to build the church of St Saviour’s as a chapel of ease for one of the poorest districts in Plymouth. The foundation stone was laid in April 1863, and the church was consecrated in October 1870.[19] By that time, Isaac had lost his position as the incumbent-designate, although he was serving as the evening lecturer. Instead, he assumed the role of chaplain at the Royal Albert Hospital in 1869.[20]

Charles Chapel, Plymouth

In November 1870, it was announced that Isaac would become the new incumbent of Charles Chapel, succeeding Rev. Frederick Courtney, who had moved to Glasgow.[21] The living, which was in the gift of Rev. Henry Addington Greaves, M.A., and worth £250 a year, had been held by Isaac’s half-brother, William, from 1846 until 1850.[22] Following his appointment, Isaac resigned from his position as the hospital’s chaplain, giving three months’ notice.[23]

Marriage and family matters

His new position may have prompted him to marry, as, on 8 April 1871, he married Mary Prichard at Clifton.[24] She was the daughter of Henry Prichard, a comb and horn manufacturer, who lived with his second wife at 3 Worcester Terrace, an impressive neo-classical terrace designed by Charles Underwood.

Mary joined Isaac at 3 Moor View Terrace. Their son, Robert Henry, was born on 5 September 1872, and their daughter Mary on 25 June 1874.[25] Isaac’s mother and sister, Rebecca, who had lived with him in Plymouth, returned to Totnes, where they lived at Philadelphia Villa, Bridgetown.[26] In October 1872, Rebecca married Richard Guard, whose first wife had been the widow of Rebecca’s half-brother, Thomas. Thirty-six years older than Rebecca, Richard had been a rope manufacturer in the Royal Dockyard at Plymouth, where he had prospered after inventing new rope-making machinery.[27] Upon his death in 1884, his estate probably passed to Rebecca as he did not leave a will.[28]

Isaac’s mother died at Totnes on 11 October 1875, leaving an estate valued at “under £200,” which she bequeathed entirely to Rebecca.[29] Upon her death, Isaac inherited £1,000 under the terms of his father’s will, and Rebecca, £1,600. When Rebecca died in March 1894, she left an estate valued at £3,105 19s 9d, which she mainly divided between her brothers, Edwin and Isaac.[30]

Although Isaac served a poor parish, his private means enabled him to live in an affluent area. In about 1880, he commissioned the building of a six-bedroomed detached villa on a third of an acre of land fronting Lipson Road. The property, which he named Trusham Villa, stood opposite Beaumont Park and commanded magnificent views of the Harbour and Cattewater.[31] It had up-to-date modern conveniences and was connected to the telephone exchange in 1881.[32]

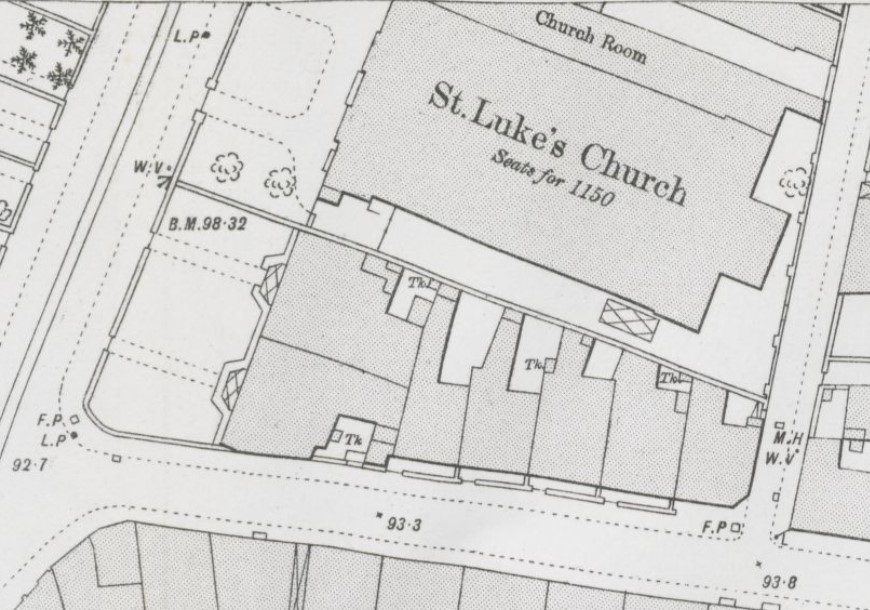

St Luke’s, Plymouth

In 1874, Charles Chapel was designated a parish church under the name St Luke’s and was assigned an ecclesiastical district with a population of about 4,000.[33] The church was an oblong structure with a gallery around three sides and long, round-headed windows. A chancel was added in 1878 at a cost of about £490.[34] Isaac’s services focused on the spoken word. In 1883, he told a conference of the Evangelical Protestant Union that “The practice of intoning the service, or adopting a musical service, or wearing the surplice in the pulpit did not tend to keep people at the footstool of grace.”[35]

Isaac was a diligent and hardworking minister who served single-handedly for twenty-four of his twenty-seven years. Each week, he delivered three sermons and two cottage lectures and attended three Bible classes. He regularly visited the sick and dying, earning the trust and confidence of parishioners, who continued to support the church financially despite their modest means.[36] In 1882, when he declined to accept the more lucrative living of St Breward in Cornwall offered to him by the Dean and Chapter of Exeter, his parishioners showed their appreciation by presenting him with a purse of 100 sovereigns and an address signed by 164 members of the congregation.[37]

He was an ardent and energetic supporter of missionary work both at home and abroad, often attending meetings of organisations such as the Church Missionary Society, the London Missionary Society, the Zenana Missionary Society and the Church Pastoral Aid Society.[38] He also supported local Christian organisations, including the Plymouth Town Mission, the YMCA, and the Plymouth Railway Men’s Christian Association.[39]

He also promoted temperance, establishing a temperance society at St Luke’s in 1884.[40] When this society joined the Plymouth Band of Hope Union in 1890, it had 120 members and an average attendance of 90.[41] When the Three Towns and District Temperance Federation put questions to all the guardian candidates in 1894, Isaac was among those who gave favourable replies.[42]

Isaac was open to cooperating with Protestant Nonconformists. In the 1870s, while on holiday in Downderry, Cornwall, he held Sunday services in a barn that Wesleyans used for worship, conducting them while dressed in a loose alpaca coat.[43] In about 1876, he conceived the idea of an annual unsectarian Christian conference in Plymouth, and this ran for several years.[44] In the 1880s, he regularly attended meetings as part of a New Year’s united prayer initiative organised by various religious denominations. [45] He also regularly attended an annual interdenominational evangelical conference in Clifton.[46] A leading figure in this conference was Rev. James Ormiston, the rector of St Mary Le Port, Bristol, with whom Isaac developed an enduring friendship.

Isaac’s intense Protestantism was accompanied by explicit and sustained opposition to ritualism and Roman Catholic influence. From the early 1880s until late in life, he regularly attended meetings and conferences organised by groups such as the Evangelical Alliance and the Evangelical Protestant Union, which aimed to eliminate ritualism from the Church of England.[47] When he appeared as a speaker, he invariably used the language of bitter conflict, as, for example, in 1886, when he appealed to his audience not to compromise in the slightest manner with the enemy.[48] This fervent Protestantism extended to his joining the Orange Order, where he became the first Grand Master of a new West of England Province in 1892.[49] He established a lodge in Plymouth and regularly attended dinners and other events, one as far afield as Newcastle-upon-Tyne.[50] The movement was relatively strong in Plymouth during the 1890s, with about 200 people attending a tea and concert in 1893.[51]

Isaac’s religious outlook can be understood as the product of several reinforcing influences rather than a single determining cause. He was born into a family with an established tradition of Protestant militancy: in 1829, his uncle, Rev. John Hawkes, publicly announced his intention to secede from the Established Church in protest at the Catholic Relief Bill, a gesture that illustrates the depth of anti-Catholic feeling within the family.[52] His theological studies at St Aidan’s College further shaped this inheritance, as the college was strongly evangelical and often described by contemporaries as Puritan in ethos. These early influences were then intensified by broader developments within the Church of England itself. The rise of ritualism from the mid-nineteenth century provoked sustained resistance among evangelicals, and Isaac’s ministry unfolded within that climate of religious tension. Over time, his views were reinforced through continued involvement in evangelical and Protestant organisations, which provided both intellectual validation and practical encouragement for a theology firmly grounded in Pauline doctrine and Protestant identity.

Isaac combined exacting religious views with a social conscience. He served for fifteen or sixteen years as a member of the Plymouth Court of Guardians, taking a keen interest in the operation of the Poor Law and attending meetings regularly.[53] He also supported the South Devon and Cornwall Blind Institution and the Plymouth, Devonport and Stonehouse Female Penitentiary for many years.[54]

During his tenure as a Poor Law Guardian, he voted at least twice against accepting a free invitation from the local theatre for the workhouse children to attend a Christmas pantomime. He believed theatres were morally wrong, and he felt the experience would train them to enjoy things that would, in the future, be harmful to them and beyond their means.[55]

Through 1897, Isaac continued serving as a Poor Law Guardian, but the newspapers report no other activity for him, except that he preached at Exeter Cathedral on the evening of Sunday, 10 October 1897.[56] Perhaps he was exhausted by his heavy workload in a parish gripped by immense social and economic problems. In February 1898, it was announced that he had been appointed as the vicar of Ironbridge in Shropshire.[57] He preached his farewell sermon on Sunday, 17 April 1898, and his parishioners presented him with a purse containing £156, a silver salver, an illuminated address and other presents.[58] His house, Trusham Villa, was sold by auction on 5 April 1898.[59]

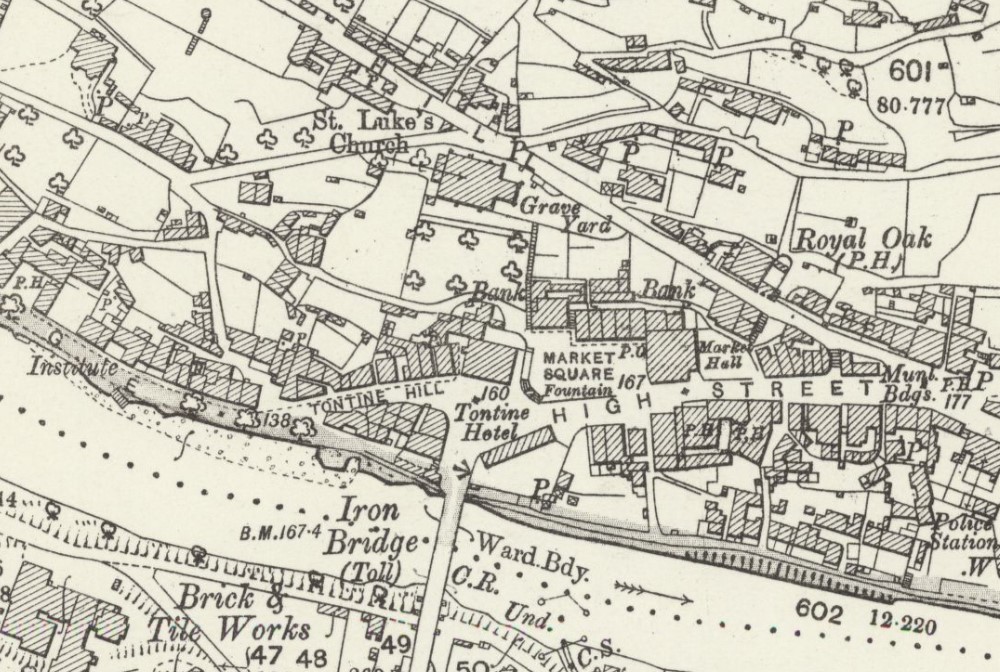

Ironbridge

At Iron Bridge, he succeeded Rev. George Wintour, who resigned at the age of about 77 after serving for 33 years.[60] Wintour had been high church, embracing innovations such as wearing a coloured stole, crossing himself, and installing a cross and banner in the church, which alienated many people who regarded them as Romish.[61] Isaac was probably chosen because his evangelical views stood in marked contrast to Wintour’s High Churchmanship.

Isaac was presented to the living by Rev. George Edward Yate, M.A., the vicar of Madeley, who was the patron because the parish was formed out of Madeley in 1845.[62] The net yearly value of the benefice in 1891 was £170, which was low. Ironbridge was a market town with a population of 2,739 in 1891. It had a railway station, several dissenting chapels, a church school, a Wesleyan school, and the Madeley workhouse.[63] The church, built in 1836, accommodated about 1,100 people.[64]

Under Wintour, church attendance had been low. For instance, on one Sunday in February 1895, only six people, besides the choir, attended the morning service, and about thirty the evening service. That day, Wintour announced that, for the remainder of the winter, the Sunday morning service would be held in the Mission Hall rather than in the church.[65] However, the following year, alterations were made to the church that made it brighter and more welcoming, and a large congregation attended the reopening service.[66]

Isaac’s appointment was announced in February 1898, and the following month, he travelled to Ironbridge to meet the churchwardens.[67] On 11 April, he wrote to them to share his thoughts about the future, stating that he felt at home with them and expressing his wish for continuity with the churchwardens and officials. He also revealed his earnest evangelical approach:

“I shall by God’s grace seek the welfare and real prosperity of the people—soul and body—and not be satisfied with a name or show. Thus, when I come, may it be in the fullness of the blessing of the Gospel of Christ.”[68]

On 24 April 1898, Isaac read himself in at Ironbridge “before a large and fashionable congregation,” preaching extempore with a clear, powerful voice on the text “Search the Scriptures, for they are they which testify of me.”[69]

The churchwardens and other churchgoers were eager to ensure that Isaac felt welcomed and supported. On 19 May 1898, they organised a special meeting to discuss matters arising from his arrival, including the cost of repairing the rectory, which legally fell on Wintour but which he was unable to pay. They agreed to form a committee to raise the required sum and, at the same time, £49 to build a choir vestry. The meeting also decided to welcome Isaac with a tea and entertainment.[70]

This public event was held at the National Infants’ Schoolroom on the evening of 8 June, with about 200 attendees, including several local Anglican clergymen and the town’s Wesleyan minister. After the tea, the churchwardens and several others expressed a warm welcome to Isaac, and presented him with a purse of 55 guineas to pay for the rectory dilapidations. In his brief reply, he thanked them for the gift, stated that he had come to that parish to work, and asked for all the help they could provide.[71]

Isaac had soon realised there was much work to do. In an effort to increase church attendance, he began a programme of regular, systematic pastoral care, including home visits and readings, and organised several church groups, such as the Women’s Meeting, the Working Girl’s Club, and the Men’s Meeting.[72] In 1900, he engaged a scripture reader and organised the installation of a new organ.[73]

He soon saw the situation improve. The church collections increased from £60 2s in 1897/98 to about £119 in 1898/99 and to £137 2s 5d in 1899/00.[74] The number of sidesmen appointed at the annual vestry meeting increased from six in April 1898 to twelve in April 1899 and to thirteen in April 1901.[75] In April 1900, Isaac reported that the congregations were “in a healthy condition, numerically and practically,” but acknowledged there was still much work to be done; hence, he had secured a scripture reader.[76] In April 1903, he looked back over his five years and said that the parish was in a better state than when he came and that the finances were better than they had been for a quarter of a century.[77]

Despite having strong views, Isaac was willing to compromise. In April 1900, when the vestry discussed changing the hymn books, Isaac was in favour of replacing Hymns Ancient and Modern, which he considered Popish, with the Hymnal Companion. However, when he encountered strong opposition, he relented and acknowledged that the two collections shared 300-400 hymns and that he could omit those he found objectionable.[78]

He continued to support missionary work at home and abroad by chairing or lecturing at meetings of the Church Missionary Society, the London Missionary Society, and the Zenana Missionary Society.[79] He also formed a local branch of the British and Foreign Bible Society.[80]

His duties included overseeing religious education at the National School. In 1903, he also acted as the school’s correspondent, serving as its formal intermediary with the Education Department and government inspectors.[81] In 1906, he attended a meeting at Coalbrookdale to protest the Liberal Government’s Education Bill, which proposed transferring control of Church schools to local authorities. In seconding the resolution condemning the measure, he expressed the hope that “the wretched bill would never become law.”[82]

Isaac’s time at Ironbridge coincided with a period of intense anti-ritualist campaigning, and he continued to support the cause, attending five notable events. In August 1898, he attended a garden party addressed by the anti-ritualist campaigner, John Kensit, and in July 1902, he attended a meeting of the Shrewsbury branch of the recently formed Ladies’ League for the Defence and Promotion of the Reformed Faith of the Church of England.[83] In April 1900, he attended the annual meeting of the Worcester branch of the National Protestant Church Union.[84] In December 1902, he preached in St Julian’s Church, Shrewsbury, for the National Protestant League.[85] In April 1904, he spoke on “The communion of the Holy Ghost” at the seventeenth annual meeting of the South Midland Protestant Union at Tewkesbury.[86] Taken together, these appearances indicate sustained engagement within organised evangelical and anti-ritualist networks, chiefly at a regional level rather than as a national figure.

While living at Ironbridge, Isaac volunteered to serve as the chaplain to the workhouse, a position that commanded a salary of £30 per annum.[87] He treated the inmates with compassion, giving them pictures and ornaments, attending their Boxing Day dinner, and providing them with tea, sugar, and tobacco.[88] His services were well-attended; in March 1903, he reported to the Guardians that the average attendance at his Sunday services was 70.[89]

After nine years of service at Ironbridge, Isaac decided to resign. During the Sunday service on 24 February 1907, he told the congregation that he had submitted his resignation to the bishop.[90] He also tendered his resignation as workhouse chaplain.[91] His parishioners held a farewell party for him in the Parish Room on 1 May, at which they presented him with an illuminated address, an album of subscribers’ names, and a cheque. Thomas Law Webb, a local doctor who acted as chairman, alluded to Isaac’s great kindness to the poor and suffering, his noble character, and his love of scripture. Rev. Charles Benjamin Crowe, the vicar of Coalbrookdale, spoke about Isaac’s high character, the faithfulness of his ministry, and his friendly disposition.[92]

Isaac preached his last farewell sermons at St Luke’s Church on 12 May 1907, and he marked his retirement by presenting the church with two carved oak chancel chairs.[93]

Move to Weston-super-Mare

Isaac and his family moved to Weston-Super-Mare. Crockford’s for 1908 recorded the family’s address as Queen’s Rest, Ashcombe Gardens, while the 1911 census recorded them living in a seven-room house named Morwenstow at 31 Hill Road.[94]

Isaac was not ready to retire altogether. On 19 May 1907, he took the services at St Silas, Bristol, where the vicar, Frederic John Horefield, was a leader of the Christian Endeavour movement.[95] Three months later, he took the Sunday services at St Mary Le Port Church, where his old friend James Ormiston was the rector.[96] However, it was Hardington Mandeville that provided him with a sustained opportunity for his ministry.

Hardington Mandeville

Rev. Henry Holditch Cleife, the rector of Hardington Mandeville, appears to have formed part of Isaac’s evangelical network, the two men having known one another during their years in Plymouth. When Cleife fell ill in the summer of 1908, he asked Isaac to cover for him, evidently preferring an experienced substitute whom he trusted. Cleife’s illness prevented him from fulfilling his official duties for about a year; during this period, his only recorded public appearance was a brief attendance at a temperance meeting in the schoolroom in November 1907.[97] The precise nature of the arrangement requires further investigation, but the evidence suggests an informal understanding that suited both men.

Isaac first visited Hardington in August or September 1907.[98] Newspapers provide several glimpses of his time there. In 1907, he preached a missionary sermon at the church on 27 October, a sermon for the Church of England Temperance Society (CETS) on 24 November, and chaired a CETS meeting on 25 November.[99] In 1908, he preached a sermon for the Jews Society on 5 April, two sermons on Easter Day, and sermons for Harvest Thanksgiving on 20 September 1908.[100] He also attended three garden parties at the rectory in 1908: one for the Yeovil YMCA on 27 June, another for the choir of Christ Church, Yeovil, on 4 July, and one to celebrate Cleife’s 25 years at Hardington on 25 July.[101]

Isaac’s daughter, Mary, probably visited the village in December 1907, as the Western Chronicle recorded “Miss M. Hawker” among the ladies who helped Mrs Cleife at the first Sunday School Christmas party held at the rectory.[102]

His involvement with Hardington ended in March 1909. On Saturday, 27 March 1909, members of the Bible Classes presented him with a travelling bag and the following day, he preached at services in aid of Crewkerne Hospital.[103]

Church activities at Weston-super-Mare

During this period, he attended at least four church events at Weston. He attended a meeting of the British and Foreign Bible Society at the Assembly Rooms on 24 October 1907.[104] He presided at a large Bible Class for men at Ashcombe Park Mission Room on 17 February 1908 and attended a meeting at the Christ Church Mission Room for Irish Church Missions on 28 April 1908.[105] On 26 October 1908, he was on the platform at a meeting of the Protestant Reformation Society at the Town Hall.[106]

Later life

From March 1910 until September 1916, when Ormiston died, Isaac took many Sunday services at St Mary Le Port.[107] This may have required him to stay overnight in Bristol, as the 1911 census of Sunday, 2 April 1911, recorded him as a visitor at 3 Redland Court Road, staying with a seventy-two-year-old widow and her daughter.[108]

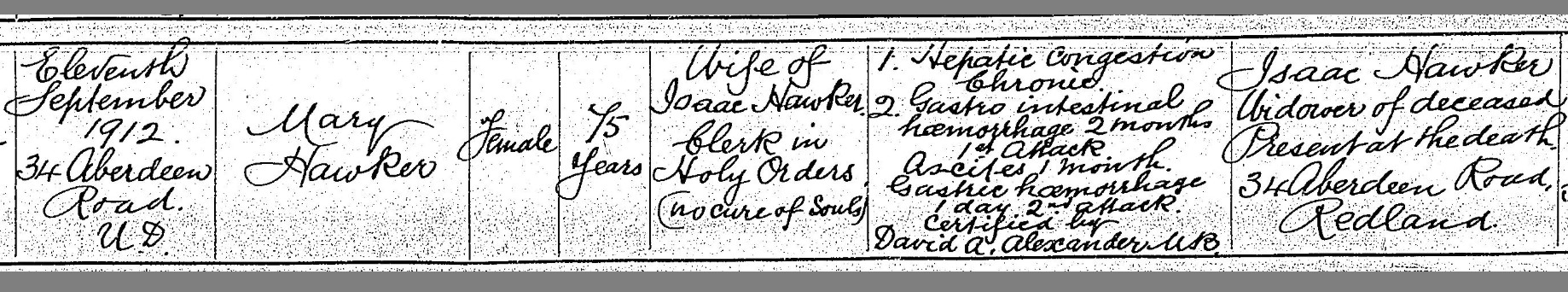

Between April 1911 and September 1912, Isaac and his family moved to Cotham, an affluent, leafy inner-city suburb of Bristol, initially residing at 32 Aberdeen Road. Mary died there on 11 September 1912 at the age of 75. Her death followed a prolonged illness marked by chronic liver disease, recurrent internal bleeding, and ascites, and was ultimately caused by a sudden acute haemorrhage.[109] She was buried at Arno’s Vale Cemetery on 14 September.[110] Isaac and Mary were married for 41 years, but she is rarely mentioned in the newspapers of the period, suggesting that she led a retiring life.

After Mary’s death, Isaac and his two adult children lived at “Fairland Villa” at 7 Clare Road until September 1915, and then at 31 Freemantle Road. Both residences were substantial properties with nine rooms.[111]

By this time. Isaac was less active. His last appearance at a Clifton Conference was in October 1909.[112] He attended a few Y.M.C.A. meetings and delivered an address entitled “I have a message for thee” in June 1915.[113] However, his role as a committed participant in Protestant organisations continued. He attended a meeting of the Bristol and Clifton Protestant League in June 1914, chaired a lecture by John Kensit’s son in March 1916, and presided over a Church Association meeting in September 1916.[114] He also attended an Evangelical Alliance meeting at the Church Missionary Hall in Park Street in January 1917.[115] No evidence exists to show that his religious message changed in response to the war. In 1916, when thousands of servicemen were being killed every day, he told a meeting that one of the greatest curses of the day was the neglect of the sabbath.[116]

Isaac died at his home on 20 April 1922 at the age of 87, leaving an estate valued at £5,611 15d. He left his son, Robert, an annuity of £80 payable monthly, and the remainder to his daughter, Mary.[117]

Mary and Robert continued living at 31 Freemantle Road, and for part of that time, Robert worked as a warehouseman and salesman.[118] Mary died in 1942, and Robert in 1955. Neither of them married.

Conclusion

Isaac Hawker’s career illustrates the strengths and limitations of late Victorian and Edwardian evangelical Anglicanism at the parish level. He was an able, hardworking, and conscientious clergyman, capable of sustaining demanding ministries for extended periods in poor and socially deprived districts. At both Plymouth and Ironbridge, he improved financial stability, encouraged participation, and earned genuine loyalty from many parishioners, particularly the poor. His civic and charitable work was deeply informed by his Christian beliefs and ethical values.

At the same time, Hawker’s identity was shaped by an intense Protestantism that left little room for compromise. This was accompanied by an austere Puritanism that jarred with the many aspects of popular culture.

In later life, as his public activity diminished, he remained consistent in his outlook, showing little sign of modifying his religious priorities in response to the First World War or other social and political changes. Taken as a whole, his life offers a revealing case study of an evangelical clergyman whose ministry embraced local parish practice and engagement with national religious movements.

References

[1] Transcripts of Trusham baptisms on the Trusham village website.

[2] North Devon Journal, 13 January 1848, p.3; Exeter Plying Post, 5 November 1846, p.2.

[3] Bristol Times and Mirror 3 October 1916 p.2.

[4] The will of Rev. Thomas Hawker, dated 9 November 1846, proved in London on 24 February 1848.

[5] The will of Rev. Thomas Hawker, dated 9 November 1846, proved in London on 24 February 1848. It is noteworthy that his sons, Henry and Edwin, moved to London to work as chemists.

[6] Charles, Plymouth, burial register; family reconstitution from parish registers.

[7] The death certificate of Thomas Hawker; the death certificate of Emma Hawker; West of England Conservative, 1 January 1851, p.5; Western Times, 3 May 1851, p.6. Thomas was 68, Emma was 24, William was 33, and Stafford was 21. William was married and living in Plymouth at the time of his death.

[8] HO 107, piece 1874, folio 39, p.19.

[9] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 30 June 1838, p.3.

[10] HO107, piece 1872, folio 343, p.30.

[11] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1908, p. 648; Globe, 27 September 1859, p.5 (name printed as “J. Hawker.”)

[12] Morning Herald (London), 25 September 1860, p.3.

[13] Western Morning News, 14 November 1870, p.2; Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1908, p. 648; Shepton Mallet Journal, 1 November 1889, p.7.

[14] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1908, p. 648.

[15] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1908, p. 648; London Evening Standard, 5 September 1866, p.7; Oxford Journal, 21 March 1868, p.7.

[16] Shields Daily Gazette, 30 May 1861, p.6.

[17] Oxford Journal, 21 March 1868, p.7.

[18] Oxford Journal, 15 February 1868, p.7.

[19] Western Morning News, 24 October 1870, p.2; 25 October 1870, p.4.

[20] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1908, p. 648.

[21] Western Morning News, 14 November 1870, p.2.

[22] Western Morning News, 8 November 1870, p.2; Western Courier, West of England Conservative, Plymouth and Devonport Advertiser, 30 September 1846, p.3; 25 September 1850, p.5.

[23] Western Morning News, 30 November 1870, p.4.

[24] Western Daily News, 19 April 1871, p.4.

[25] 1939 Register.

[26] North Devon Journal, 14 October 1875, p.8.

[27] Totnes Weekly Times, 1 November 1884, p.2.

[28] Totnes Weekly Times, 1 November 1884, p.3.

[29] North Devon Journal, 14 October 1875, p.8; the will of Agnes Hawker, dated 27 May 1857, proved at Exeter on 10 November 1875.

[30] The will of Rebecca Ellen Guard, dated 5 October 1892, proved in London on 26 April 1894. She appointed Isaac as her sole executor and bequeathed him the remaining half of her East Indian Railway Company property, her furniture, plate, books, and money at interest standing in her name, along with any funds from the East Indian Railway Co. office in London then in use for her benefit.

[31] Western Morning News, 24 March 1898, p.1.

[32] Western Morning News, 14 October 1881, p.1.

[33] Western Daily Mercury, 14 July 1874, p.4.

[34] Western Daily Mercury, 12 April 1878, p.4.

[35] Manchester Courier, 12 October 1883, p.6.

[36] Western Daily News, 16 February 1898, p.5

[37] Royal Cornwall Gazette, 21 April 1882, p.7; Express and Echo, 2 June 1882, p.3.

[38] Western Morning News, 2 June 1885, p.4; Western Morning News, 16 March 1895, p.4; Western Morning News, 10 Oct 1893, p.5; Western Morning News, 24 Nov 1894, p.8; Western Morning News, 22 October 1895, p.3; Western Morning News, 27 November 1895, p.5; Western Morning News, 29 May 1878, p.4; Western Daily Mercury, 20 April 1880, p.2; Western Morning News, 20 November 1894, p.3.

[39] Western Daily Mercury, 18 January 1889, p.8; Western Morning News, 14 November 1893, p.3; Western Morning News, 31 October 1879, p.3;

Western Morning News, 1 December 1888, p.5; Western Morning News, 27 September 1894, p.5; Western Morning News, 21 January 1895, p.3; Western Morning News, 25 May 1888, p.5; Western Morning News, 5 February 1890, p.6.

[40] Western Morning News, 5 October 1881, p.5;

[41] Western Morning News, 6 March 1890, p.5.

[42] Western Morning News, 15 December 1894, p.8.

[43] East Cornwall Times and Western Counties Advertiser, 29 July 1876, p.4.

[44] Western Morning News, 16 October 1878, p.3.

[45] Western Morning News, 4 January 1883, p.3; 1 January 1885, p.5; 5 January 1887, p.5; 9 January 1889, p.5.

[46] Western Daily Press, 9 October 1884, p.5; Bristol Mercury, 9 October 1885, p.8; Bristol Mercury, 27 October 1886, p.4; Western Morning News, 29 October 1886, p.5; Western Daily Press, 5 October 1888, p.5.

[47] Western Morning News, 2 May 1882, p.4; Western Morning News, 30 October 1885, p.6; Western Morning News, 24 September 1888, p.8; Manchester Courier, 12 October 1883, p.6; Western Morning News, 18 October 1889, p.8; Manchester Courier, 16 October 1891, p.8; Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 12 October 1894, p.5; Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 25 April 1895, p.3.

[48] Shepton Mallet Journal, 5 November 1886, p.5.

[49] Liverpool Daily Post, 22 July 1892, p.7.

[50] Belfast Weekly News, 11 July 1896, p.7.

[51] Western Morning News, 9 November 1893, p.5.

[52] Bristol Mirror, 23 May 1829, p.4.

[53] Western Morning News, 16 February 1898, p.5.

[54] Newspaper reports show that Isaac attended at least twelve annual meetings of the Devon and Cornwall Blind Institution between 1879 and 1895; Western Morning News, 26 May 1877, p.3; Western Morning News, 17 April 1885, p.5; Western Morning News, 18 April 1891, p.5.

[55] Western Morning News, 9 January 1895, p.3; 12 January 1938, p.6 (republishing a news item from 1888).

[56] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 9 October 1897, p.3.

[57] Globe, 24 February 1898, p.3.

[58] Western Morning News, 19 April 1898, p.5; Wellington Journal, 23 April 1898, p.7.

[59] Western Morning News, 5 April 1898, p.1.

[60] Wellington Journal, 19 February 1898, p.7

[61] Ironbridge Weekly Journal and Borough of Wenlock Advertiser, 19 April 1879, p.5.

[62] Kelly’s Directory of Hereford & Shropshire, 1895, p. 105.

[63] Kelly’s Directory of Hereford & Shropshire, 1895, p.105.

[64] Wellington Journal, 17 October 1896, p.7.

[65] Shrewsbury Chronicle, 15 February 1895, p.7.

[66] Wellington Journal, 17 October 1896, p.7.

[67] Globe, 24 February 1898, p.3; Wellington Journal, 16 April 1898, p.7.

[68] Wellington Journal, 16 April 1898, p.7.

[69] Wellington Journal, 30 April 1898, p.7.

[70] Wellington Journal, 21 May 1898, p.7.

[71] Wellington Journal, 11 June 1898, p.6.

[72] Wellington Journal, 4 May 1907, p.11.

[73] Wellington Journal, 21 April 1900, p.11; 12 May 1900, p.11.

[74] Wellington Journal, 16 April 1898, p.7; 1 April 1899, p.7; 21 April 1900, p.11.

[75] Wellington Journal, 16 April 1898, p.7; 1 April 1899, p.7; Shrewsbury Chronicle, 19 April 1901, p.8.

[76] Wellington Journal, 21 April 1900, p. 11.

[77] Wellington Journal, 18 April 1903, p.11.

[78] Wellington Journal, 1 April 1899, p.7.

[79] Wellington Journal, 26 November 1898, p.7; Wellington Journal, 18 February 1899, p.7; Wellington Journal, 22 April 1899, p.6; Western Daily Press, 9 July 1906, p.6; Wellington Journal, 9 December 1899, p.7; Wellington Journal, 12 September 1903, p.11; Wellington Journal, 13 January 1906, p.11; Wellington Journal, 9 July 1898, p.7; Wellington Journal, 28 October 1899, p.7; Wellington Journal, 26 October 1901, p.11; Wellington Journal, 24 October 1903, p.11.

[80] Wellington Journal, 24 November 1900, p.11; Wellington Journal, 1 November 1902, p.11; Wellington Journal, 27 October 1906, p.11.

[81] Wellington Journal, 20 June 1903, p.10.

[82] Wellington Journal, 16 June 1906, p.7.

[83] Bridgnorth Journal, 20 August 1898, p.7; Shrewsbury Chronicle, 1 August 1902, p.5.

[84] This was formerly a branch of the Protestant Churchmen’s Alliance but applied for affiliation with the National Protestant Church Union in 1893.

[85] Wellington Journal, 13 December 1902, p.7. The National Protestant League was founded in London in 1850; the Shrewsbury Lodge began in 1891.

[86] Gloucester Journal, 30 April 1904, p. 7. His talk was based on Saint Paul’s Trinitarian blessing for the Corinthian Church. The Protestant Union for the Defence and Support of the Protestant Religion and the British Constitution, as established at the Glorious Revolution of 1688, was established in 1813.

[87] Wellington Journal, 19 March 1898, p.8.

[88] Wellington Journal, 9 July 1898, p.8; 31 December 1898, p.7; Shrewsbury Chronicle, 11 January 1901, p.8.

[89] Wellington Journal, 28 March 1903, p.11.

[90] Wellington Journal, 2 March 1907, p.11.

[91] Wellington Journal, 9 March 1907, p.11.

[92] Wellington Journal, 4 May 1907, p.11.

[93] Wellington Journal, 18 May 1907, p.11; 11 May 1907, p.11.

[94] RG14, piece 14604

[95] Western Times, 23 June 1908, p.6; Sheffield Independent, 21 September 1911, p.5.

[96] Western Daily Press, 2 October 1916, p.7.

[97] Western Chronicle, 29 November 1907, p.6.

[98] Western Chronicle, 31 July 1908, p. 5; 2 April 1909, p.6.

[99] Western Chronicle, 1 November 1907, p.6; 29 November 1907, p.6.

[100] Western Chronicle 10 April 1908, p.6; 24 April 1908, p.6; 25 September 1908, p.5.

[101] Western Chronicle, 3 July 1908, p.6; 10 July 1908, p.5; 31 July 1908, p.5.

[102] Western Chronicle, 27 December 1907, p.6.

[103] Western Chronicle, 2 April 1909, p.6; Wellington Journal, 10 April 1919, p.11.

[104] Weston-super-Mare Gazette, 26 October 1907, p.5.

[105] Weston-super-Mare Gazette, 22 February 1908, p.3; 9 May 1908, p.2.

[106] Weston-super-Mare Gazette, 28 October 1908, p.3.

[107] Bristol Times and Mirror, 7 October 1916, p.17; Bristol Times and Mirror, 16 September 1916, p.6.

[108] RG14, piece 15074.

[109] The death certificate of Mary Hawker.

[110] Bristol Times and Mirror, 14 September 1912, p.22.

[111] RG14, piece 14862; RG14, piece 14863.

[112] Western Daily Press, 7 October 1909, p.3.

[113] Western Daily Press, 9 February 1912, p.5; Bristol Times and Mirror, 26 March 1912, p.6; Western Daily Press, 9 June 1915, p.5.

[114] Western Daily Press, 20 June 1914, p.7; 9 March 1916, p.5; 27 September 1916, p.3.

[115] Bristol Times and Mirror, 9 January 1917, p.3.

[116] Western Daily Press, 27 September 1916, p.3.

[117] The will of Rev. Isaac Hawker, dated 22 February 1917, proved in London on 17 June 1922.

[118] 1939 Register; National Probate Calendar; Western Daily Press, 13 March 1942, p.4; Bristol Evening Post, 6 December 1955, p.19.