Introduction

Jabez White lived at Hardington Marsh from about 1906 to 1910 during a transitional phase of his life, following the collapse of his business at East Coker. Born in Wiltshire, he moved to East Coker in the 1870s, where he became a prominent local tradesman, combining baking, milling, and small-scale farming with long service as a parish officer and participation in local voluntary organisations. His life was marked by repeated strain: the early death of his first wife after a prolonged illness, the loss of their twin sons in infancy, several legal disputes, and eventual bankruptcy. He was widely regarded as respectable and capable; however, surviving evidence suggests that his business practices were often informal and his leisure life was often chaotic. Jabez’s story highlights both the opportunities and vulnerabilities faced by independent rural traders in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Childhood

Jabez was born in 1851 at Corsley, a village of about 1,500 inhabitants, three miles east of Frome.[1] He was the youngest son of Joseph and Anne White and was named after his deceased brother, who died in 1850 at age 5.[2] His father was a grocer and baker, while his mother was the daughter of a butcher.

While still a child, Jabez lost both his mother and his first stepmother. His mother died in May 1855 at the age of 41.[3] In 1859, his father married Sarah Ann Merritt, who died in January 1864.[4] By 1871, his father had married for a third time.

Jabez may have received some formal education, as Corsley had a National School by 1855.[5] Through this education and his experience working in his father’s business, he developed numerical skills, enabling him to later serve as an assistant overseer and treasurer. [6]

Courtship and marriage

In the early 1870s, Jabez met Sophia Jane Brake from East Coker, probably while she was living in Bradford-on-Avon, as evidenced by her baptism at the parish church on November 3. Although the baptism register recorded her date of birth as February 25, 1850, she was actually born in 1851.[7] Jabez and Sophia moved to East Coker, where they married on Christmas Day in 1875.[8]

Jabez may have initially worked for his father-in-law, William Brake, who operated a bakery at Chantry. During his first year in the village, he served on the coroner’s jury enquiring into the death of Nathaniel Cox, the police constable killed by poachers in Netherton Lane.[9]

By December 1879, Jabez was running his own bakery, submitting tenders for bread to the Yeovil Board of Guardians. This was low-end production, in which he faced fierce competition. In December 1879, the Guardians accepted his tender of 6.25 pence to supply the Yeovil district, but by September 1883, this price had been driven down to 5 pence.[10]

Jabez’s bakery remained entirely separate from William Brake’s. After Brake died in July 1882, his widow immediately advertised the bakery as available to let.[11]

Family deaths

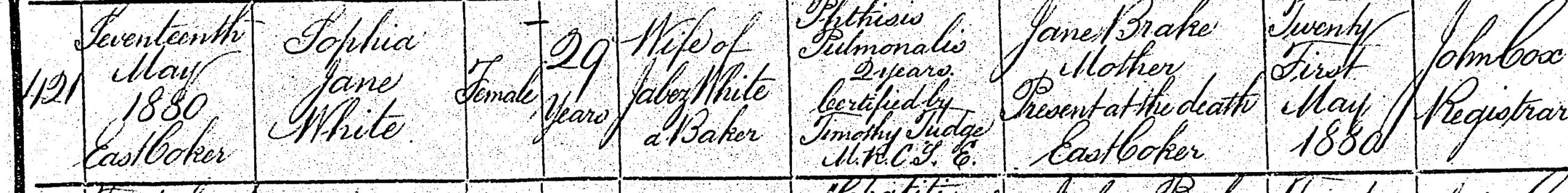

In 1876, Sophia gave birth to twins, Jabez Stanley Brake and William Joseph, but both died the following year before reaching their first birthdays.[12] Sophia died on 17 May 1880 from pulmonary tuberculosis, which had lasted for two years.[13]

Second marriage

Jabez soon entered into a new relationship with Annie Maria Hodges, the daughter of John and Amelia Ford of Bryants Farm, Pendomer. They married at Pendomer on 17 November 1880.[14] Jabez was 29, and Annie was 20. The 1881 census recorded them living at 8 Up Coker Street, East Coker, with a seventeen-year-old baker’s assistant and a twelve-year-old errand boy.[15]

Embezzlement case

In June 1884, Jabez prosecuted his former employee, John Pedwell, for embezzling £1 2s 6d. The case revealed Jabez’s casual business practices, including hiring Pedwell two years earlier without obtaining references, failing to reconcile takings with the number of loaves produced and delivered, and failing to count cash at the end of each day, sometimes leaving it on the counter overnight. According to Jabez’s testimony, despite Pedwell confessing to selling bread to casual customers and keeping the cash, he maintained that the accounts for all regular customers were accurate. However, Jabez made enquiries and found discrepancies. Pedwell, who pleaded not guilty, was committed for trial at the Quarter Sessions.[16]

At the Quarter Sessions in July, Pedwell stood trial for embezzling three sums paid to him by different customers. His defending barrister argued that while there was cause for suspicion, there was no proof of felonious intent and that mistakes could easily happen unintentionally. Under cross-examination, Jabez’s wife admitted that she had occasionally left her purse unattended for hours without Pedwell touching it. The jury struggled to reach a unanimous verdict and ultimately convicted Pedwell with a strong recommendation for mercy. He was sentenced to four months’ hard labour.[17]

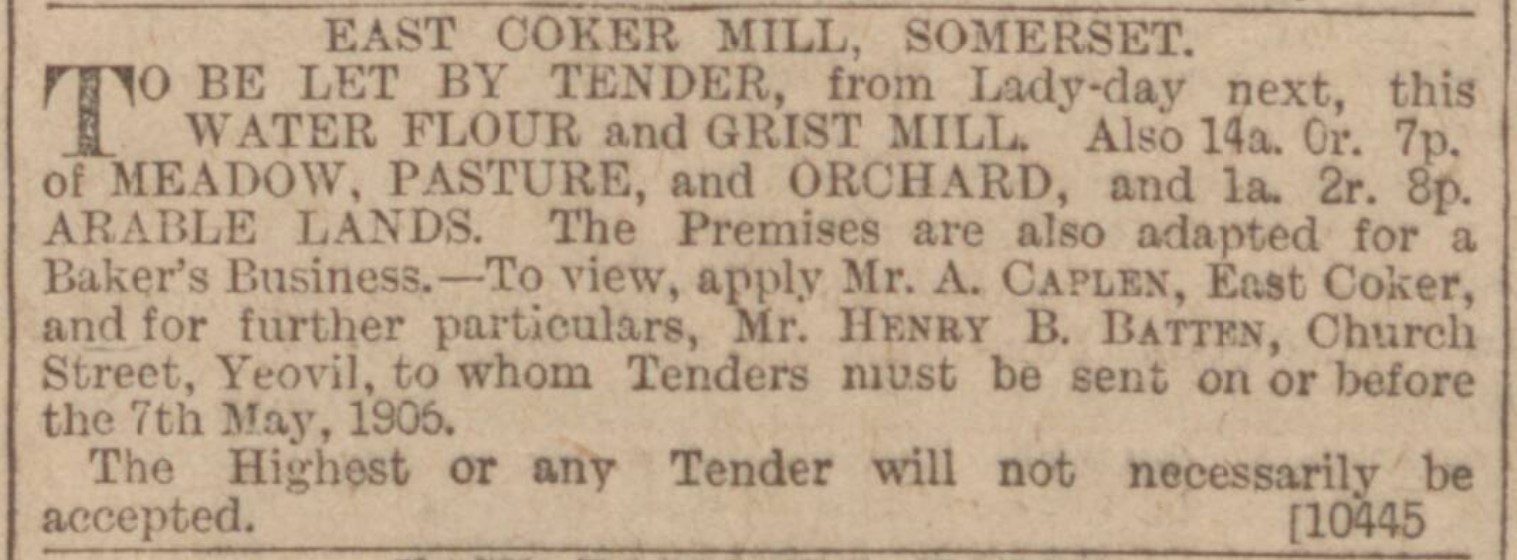

East Coker Mill

In 1887, Jabez assumed the tenancy of East Coker Mill, which included 14 acres of farmland.[18] He continued his bakery business, while also grinding corn and barley and keeping a few cows.[19] The land included orchards from which he made cider.[20]

In addition to his business, he supplemented his income through public appointments, serving as assistant overseer at East Coker from 1885 to 1903, and as Inland Revenue collector for three parishes.[21] He also served on a voluntary basis for several local organisations, including serving as treasurer of the local branch of the Ancient Order of Foresters, a member of the local Highways Board, treasurer of the East Coker burial board, and secretary of West Coker Flower Show.[22]

Jabez and Annie had no children of their own, but by 1901, Annie’s niece, Mabel Hodges, had come to live with them. It is possible that this arrangement was a form of de facto adoption, as Mabel was still living with them in 1905.

Court cases

In the 1880s, Jabez was the plaintiff in two court cases that illustrate his deftness in presenting evidence at a time when many business transactions were not recorded in writing. In May 1887, he sued James Rose, the landlord of the Dolphin Inn, Yeovil, for an alleged breach of warranty on a pig that died two days after he bought it. Although Rose denied making any warranty, Jabez called George Helliar as a witness, who claimed to have heard the warranty. The judge decided in Jabez’s favour solely on the basis that it was the word of two men against the word of one.[23]

In January 1891, when Jabez sued Thomas Guy, a Yeovil wheelwright, for overcharging him, he produced three local men to support his case, which contributed to his victory. The judge was satisfied that he had been overcharged and reduced the price payable from £5 11s to £4.[24]

However, Jabez was less successful when he took on Yeovil Corporation in 1892. He became involved in a test case concerning market tolls after selling bread within the borough on a market day without paying the required toll. The case lasted two hours at Yeovil Borough Sessions, with the solicitors for both sides arguing over borough charters and complex statutory provisions. Ultimately, the magistrates upheld the Corporation’s rights and ordered Jabez to pay a fine of 10 shillings plus costs. This would have been a considerable sum, as it would have covered the prosecution’s costs and his own legal costs.[25]

Criminal charges

The early 1900s were a difficult time for Jabez. Between 1902 and 1905, he incurred five fines for minor offences: three for driving without lights, one for being drunk on licensed premises and another for leaving his horse and cart unattended in the street.[26] Most seriously, in May 1905, he was arrested and charged with a serious and deviant crime.[27]

This incident occurred after two young labourers, Frederick Clothier (about nineteen) and Albert Rendell (seventeen), who had previously been employed by Jabez, spread malicious rumours shortly after being dismissed. These rumours reached PC George Gould, who, after speaking to Clothier and Rendell, arrested Jabez on Sunday, 7 May, at 9:15 pm. Jabez was granted bail and subsequently appeared at Yeovil County Police Court on 15 May before Mr G Troyte-Chafyn-Grove and Colonel Berkeley, local landowners and magistrates. He was defended by the solicitor, Mr J. A. Mayo.

Clothier testified that he was with Rendell at East Coker Mills on 3 May, between 2 pm and 2:15 pm, when Jabez was scraping a cow with a knife. Jabez ordered him to fetch his tools, and upon his return, he saw Jabez commit the offence. Under cross-examination by Mayo, Clothier admitted that Jabez had criticised his behaviour, given him notice to leave and deducted 3d from his pay. He denied saying, “I’ll make up a tale and pay you out for this.” Rendell corroborated Clothier’s testimony and, when cross-examined by Mayo, admitted to being previously convicted of cruelty to a horse in the same court.

Jabez conducted himself well in court. He testified that he had brought the cows from the field and taken them to a stall to clean them, standing behind them at a respectable distance. Clothier and Rendell were present for part of the time as they entered the stall to sharpen their hooks. Jabez stated that Clothier often used vulgar language, and he suspected him of theft. When he deducted a sum from Clothier’s pay, Clothier had said, “I’ll pay you out for this.” Jabez’s wife and niece, Mabel, gave supporting evidence.

After considering the evidence, the magistrates dismissed the case outright, with the chairman stating that no jury would ever convict. An attempt at applause in court, quickly suppressed, suggests that those present supported the outcome.

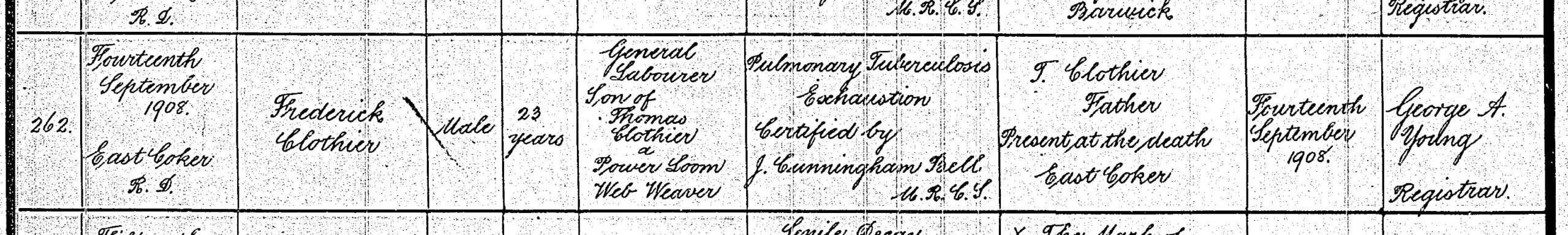

While it is easy to focus on the sensationalist aspects of this story, it can be reframed as a case of strained relations and unequal power dynamics between an employer and employee. Jabez was unhappy with Clothier’s performance, accusing him of being late in the morning and suspecting him of pilfering. On the other hand, Clothier had reason to be aggrieved at how he was treated. Jabez gave him a week’s notice and then allowed him to remain for an additional week before dismissing him with a day’s notice. He only paid Clothier on his first Saturday and at the end of his employment. He also made a deduction from Clothier’s final wages of either one shilling, as he asserted, or 3 pence, as Clothier stated, which incensed Clothier. Viewed in this light, the proceedings may reflect the escalation of grievance and mistrust between an exacting employer and a teenage labourer with limited power, possibly already in declining health. Clothier died from pulmonary tuberculosis on 14 September 1908 at the age of 23, which raises the further possibility that illness and strain contributed to the deteriorating relations.[28]

The case also suggests that officialdom had learned to approach Jabez’s testimony with professional scepticism. While Gould acknowledged that Jabez had complained to him in mid-April about Clothier stealing wood, meal, and corn, he declined to investigate, possibly believing Jabez’s accusations were unreliable and that any missing stock was likely due to sloppy business practices of the kind exposed by the embezzlement case. Two earlier cases further suggest that Jabez was capable of shaping his evidence to his advantage. When he was charged in 1878 with failing to obtain a dog licence, he claimed that he had previously informed the village postmaster that he would require one and had then forgotten about it, even producing the postmaster as a witness.[29] Similarly, in June 1903, when he was charged with driving a horse and cart at a furious pace without lights and the worse for drink, he claimed that he was driving a man home out of kindness.[30]

Bankruptcy

By early 1906, Jabez was in financial distress. In about May, he borrowed £50 from Mr Ford, with whom he had dealt for a number of years. In June, he made an offer of 3s in the pound to his creditors, which was rejected, and soon afterwards, Ford filed for a receiving order.[31]

At his public examination in July 1906, Jabez explained the circumstances that had led to his bankruptcy. He stated that he had taken on the mill about nineteen years earlier with a capital of about £200. Until ten years ago, he had been doing well, but since then, he had lost as much as he had previously gained. He attributed this decline to a lack of water, stating that on one day that year, he had ground less than two sacks of barley because water was being diverted at West Coker for road watering. He also attributed his difficulties to ill-health, which had reduced his capacity to work and deprived him of income from official duties. His liabilities amounted to just over £173, while his realisable assets were valued at about £71, leaving a deficiency of roughly £102. He emphasised that the household furniture belonged to his wife.[32]

Hardington Marsh

In 1906, Jabez and Annie left the mill and moved to Hardington Marsh, where they rented a house from Walter White and about half an acre of land from the Portman Estate.[33] They were settled there by 15 September 1906, as the East Coker parish council noted on that day that the clerk to the burial board, which was Jabez, had moved to Hardington and taken the books with him.[34]

On 1 August 1908, Jabez lent a cart or wagon to take the Bible Christian Sunday school children to Ham Hill, which suggests he may have been a chapelgoer.[35]

Jabez was a corn dealer, and his business activities included visiting local mills. In May 1908, while he was visiting a mill at Hewhill, East Coker, his large Scotch collie dog pounced on and eviscerated the miller’s much smaller dog, which had to be put down. John Lock, the miller, sued him for £2 2s in damages, while Jabez made a counterclaim for £2 for injury to his dog. At the county court, Jabez’s claim that his dog was one of the quietest ever known was met with scepticism by the judge, who retorted, “If a quiet dog does this, what will a savage one do? He gave judgment to Lock for £2 and dismissed Jabez’s counter-claim.[36]

Sherborne

In about 1910, Jabez and Annie moved to Goathill Mill, a grist mill near Sherborne, which Jabez managed, probably for the tenant of Goathills Farm.[37]

Haydon

After retiring in his seventies, Jabez and Annie moved to 379, Haydon.[38] Annie died there in January 1925, at the age of 64. Following her death, her unmarried sister, Elizabeth Hodges, moved in with Jabez to act as his housekeeper.[39]

On Sunday, 15 January 1928, Jabez went up to bed at 9:45 pm, declining Elizabeth’s offer of supper. About a quarter of an hour later, she heard noises upstairs, followed by the sound of Jabez falling down the stairs. Opening the door with difficulty, she found him lying unconscious with his feet up the stairs. She fetched three neighbours, and together they carried him to his bed. He died at about 2 am without regaining consciousness. At an inquest held two days later, a doctor testified that Jabez suffered from a disease of the mitral valve of the heart, stating that, in his opinion, his death was due to the shock of falling downstairs. The coroner returned a verdict that death was due to an accidental fall.[40]

Jabez died at the age of 77, leaving a small estate valued at £104 2s 2d. Elizabeth proved his will and may have been his beneficiary.[41]

Conclusion

Jabez’s life story shows a man struggling to earn a living as an independent trader in a society with a scant safety net to protect against failure. He operated as a legitimate businessman and held many respectable offices, yet a moral ambiguity attached to him: he was both a respectable citizen and someone capable of exploiting young employees, keeping a savage dog and, at times, inventing self-serving stories in court.

References

[1] His birth was registered in the Warminster district in Q2, 1851; Post Office Directory of Wiltshire,1855, pp.38-39.

[2] Civil registration death index; Corsley burial register.

[3] Civil registration death index

[4] Longbridge Deverill marriage register; Civil registration death index; Corsley burial register.

[5] Post Office Directory of Wiltshire,1855, pp.38-39; Corsley burial register. The 1871 census describes Jabez as a scholar (RG9, piece 1303, folio 33, p.13).

[6] RG10, piece 1932, folio 36, p.13.

[7] Civil Registration Birth Index; Bradford-on-Avon baptism register. Sophia’s birth was registered in the Yeovil registration district in Q1 1851. Her biological father may have been Israel Rendell, a landowner and sailcloth manufacturer at West Coker, who, when he died intestate in 1878, left a personal estate valued at “under £7,000.” The 1871 census recorded Sophia as staying at his house as a visitor, and when she was baptised as an adult at Bradford-on-Avon later that year, she gave her father’s name as William Brake, and his occupation as a manufacturer.

[8] East Coker marriage register.

[9] Bridgwater Mercury, 22 November 1876, p.6.

[10] Western Gazette, 26 December 1879, p.5; 28 September 1883, p.5

[11] National probate calendar; Western Gazette, 21 July 1882, p.4.

[12] Civil Registration Indexes.

[13] Death certificate of Sophia Jane White; Western Gazette, 21 May 1880, p.8.

[14] Pendomer marriage register.

[15] RG11, piece 2389, folio 6, p.5.

[16] Western Gazette, 27 June 1884, p.5.

[17] Western Gazette, 4 July 1884, p.7; England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892; John Edward Pedwell later moved to Frome, where he continued to work as a baker and married in 1888. He died in 1919.

[18] Western Chronicle, 6 July 1906, p.6.

[19] During his time at the mill, he placed many newspaper advertisements for lads or young men to help him in the bakehouse and with deliveries, or work in the mill or milk cows.

[20] Western Gazette, 19 May 1907, p.7; Western Chronicle, 9 June 1905, p.5.

[21] Dorset County Chronicle, 21 May 1885, p.9; Western Chronicle, 26 June 1903, p.5; 6 July 1906, p.6.

[22] Western Gazette, 23 September 1887, p.6; 14 February 1890, p.6; Western Chronicle, 21 September 1906, p.6; Western Chronicle, 3 August 1894, p.7; Western Chronicle, 27 August 1896.

[23] Western Gazette, 13 May 1887, p.6; 3 June 1887, p.6.

[24] Western Chronicle, 16 January 1891, p.5.

[25] Western Gazette, 8 April 1892, p.3; 6 May 1892, p.5.

[26] Western Chronicle, 5 September 1902, p.4; 9 January 1903, p.4; 5 June 1903, p.5; 5 June 1903, p.6; 19 May 1905, p.3; 3 August 1894, p.7; 27 August 1896, p.6.

[27] Western Chronicle, 19 May 1905, p.3.

[28] The death certificate of Frederick Clothier.

[29] Western Gazette, 3 May 1878, p.5.

[30] Western Chronicle, 5 June 1903, p.5.

[31] Western Gazette, 22 June 1906, p.9; Western Chronicle, 6 July 1906, p.6.

[32] Western Chronicle, 6 July 1906, p.6.

[33] Hardington Guardian valuations.

[34] Western Chronicle, 21 September 1906, p.6.

[35] Western Chronicle, 7 August 1908, p.5.

[36] Western Chronicle, 14 August 1908, p.5.

[37] In 1921, Jabez worked for John Smith Norman, a farmer who lived at Goathills Farm.

[38] Western Gazette, 20 January 1928, p.6.

[39] Western Gazette, 20 January 1928, p.6.

[40] Western Gazette, 20 January 1928, p.6.

[41] National probate calendar.