Introduction

Job Taylor was a blacksmith who ran the forge in Hardington’s High Street from about 1845 to 1869. During his time there, he spent a brief period in prison for a theft he did not commit and faced an accusation of assault from a female neighbour. After losing his first wife to tuberculosis in 1851, he raised his two sons with the help of his mother-in-law. In 1864, he married a woman from London, but she had a latent disease which would eventually manifest itself both physically and mentally. In the early 1870s, Job and his family moved to Street, where he received numerous fines for not sending his children to school. He died in 1899 at the age of 79.

Childhood at Corscombe

Job Taylor was born around 1820 at Corscombe, the fourth of ten children born to Thomas and Elizabeth Taylor. His father, Thomas, was a farm labourer.

Among Job’s brothers were John, who became a fellmonger at Bridport, and George, who became a shoemaker in Southampton and later emigrated to the USA. Among his sisters were Ruth, whose husband Eli Whitty was a baker and grocer at South Perrott and, for a time, kept the Coach and Horses Inn, and Charlotte, who was a schoolteacher at West Chelborough.

Job chose to become a blacksmith, which required him to serve a seven-year apprenticeship. He must have started at the age of fourteen or older because the 1841 census recorded him as an apprentice blacksmith living at home with his parents.

Marriage

After completing his apprenticeship, Job moved to Hardington.

On 11 August 1845, he married Dinah Ingram at Hardington. At the time of their marriage, Job was about 25, and Dinah was 22. Both signed the marriage register.

Dinah was the daughter of William and Sarah Ingram. Her father was a ship’s carpenter, and her mother had sometimes travelled with him. Dinah was born in Bristol, and her sister, Elizabeth, was born in Harbour Grace, Newfoundland.

In 1832, Dinah’s mother inherited £100 from her uncle, Abraham Genge, of Forteau Bay, Labrador.[1]

Prison sentence

In March 1846, Job was accused of stealing tools from a carpenter named Peter Hodges and spent a short time in prison before being acquitted of the crime.[2] The prison register describes him as five feet six inches tall, with a sallow complexion, dark brown hair, hazel eyes, and two small scars on his right cheek.[3]

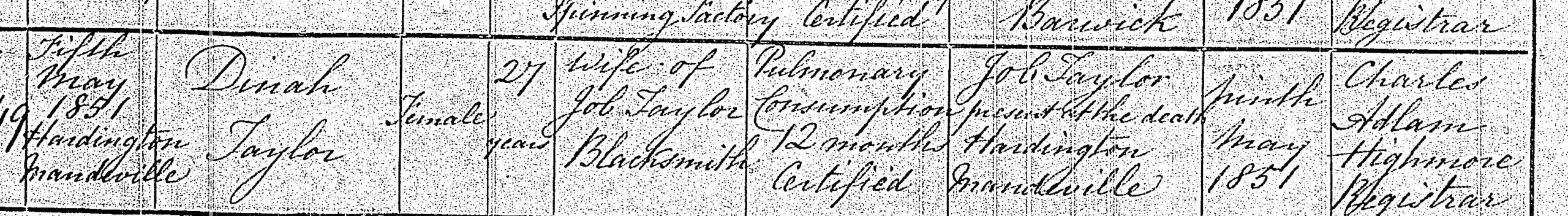

Dinah’s death

The period from 1850 to 1851 was particularly difficult for Job, as both his wife and oldest child, Emily, developed life-threatening illnesses. Dinah was diagnosed with tuberculosis in May 1850, and Emily with scrofula, likely a form of tuberculosis, in January 1851. Dinah died on 5 May 1851 at the age of 27, and Emily died on 15 July 1851 at the age of four.[4]

For thirteen years, Job raised his two remaining children, Hugh and John, with the help of his mother-in-law.

Dispute with Sarah Delamont

In 1857, Job faced more legal trouble. On 21 August 1857, he was summoned by Sarah Delamont for allegedly assaulting her. The incident occurred after Job removed an iron ring belonging to him from her little boy. Sarah became so aggressive that he had to push her away. Job produced a paper signed by five local farmers—Abraham Genge, William Genge, William White, Francis Dawe, and Thomas Genge—describing her as “very saucy and abusive”. The magistrates decided that while the assault was proven, there had been great provocation. They imposed a fine of 1s and costs.[5]

Second marriage

Job’s life took a new direction when he decided to remarry. The wedding took place at St Mary’s Church, Lambeth on 17 May 1864, and his new wife was Mary Babb. At the time, Job was about 44 years old, and Mary was 32. They were married by licence and both signed the marriage register. The witnesses were Mary’s siblings, John and Sarah.

Mary was the eldest daughter of John and Susannah Babb, who originally came from Devon. Her father worked as a tailor in Exeter for many years before moving to 2 Tenison Street, Lambeth, in the 1850s, when Mary was in her twenties.[6] Mary worked in the family business as a waistcoat maker, and many of her nine siblings were also employed there.

How Job came to meet his new wife is unknown. It is possible that they met through a matrimonial agency, which did exist in Victorian times. The reason Job felt the need to look so far for a spouse remains unanswered. Tragically, Mary had previously had at least one sexual partner from whom she contracted syphilis, although she may have been unaware of this. The condition would eventually lead to horrific symptoms, wreck their marriage and lead to her premature death.

Job’s life with Mary at Hardington

After their marriage, Mary moved in with Job at Hardington, where they lived for five years. Their first child, Charles, was born on 23 March 1866, followed by Thomas on 14 January 1868 and Job in early 1869.

Then, on 20 December 1869, Job organised a sale of his effects in preparation for leaving the village.[7]

The missing years

After leaving Hardington, Job may have kept the Railway Inn at Hendford, Yeovil. A person named Job Taylor held the licence there from July 1870 to July 1871.[8]

Job and his family have not yet been found in the 1871 census. However, his two sons from his first marriage, Hugh and John, were living in lodgings at Yeovil Marsh, where they worked as journeyman wheelwrights.

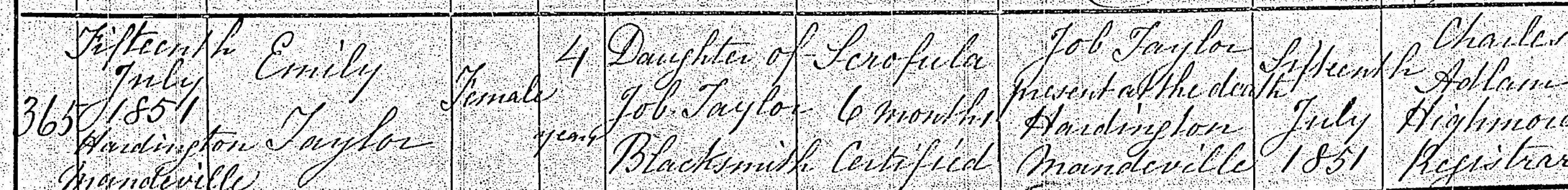

Compton Dundon

By May 1872, the family had moved to Compton Dundon, where Job worked as a blacksmith and wheelwright, possibly for John Weech, a blacksmith, or James Wallis, a wheelwright. Their son, Albert Babb, was born at Compton Dundon on 15 May 1872.[9]

Street

By February 1875, the family had moved to Street, which became their permanent home. In 1875, Mary gave birth to twins, Ernest Alfred and Mary Annie. In April 1881, Job, Mary and their six children lived in Mead Street.

Job worked as an employee rather than in his own business. In February 1875, he was a fitter; by April 1878, he was a blacksmith.[10]

Job’s home life was chaotic. From December 1876 until the end of 1886, he was fined multiple times for neglecting to send his children to school. In November 1886, Job told the court that his wife had a weak intellect, and he kept the children at home to look after her. He was advised to hire someone to look after her or have her in an asylum.[11]

In November 1880, Job’s eight-year-old son, Albert, suffered severe burns to his face after accidentally igniting some gunpowder that was stored in the family kitchen.[12]

Two of the sons left home in the 1880s: Thomas enlisted in the Royal Navy in 1884, and Charles married in 1889.

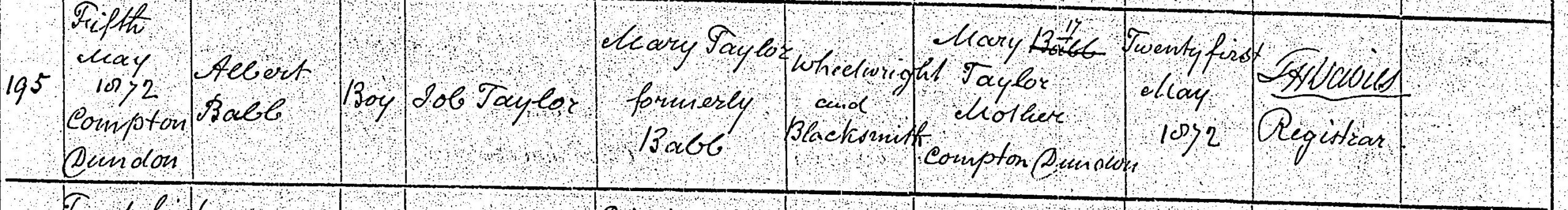

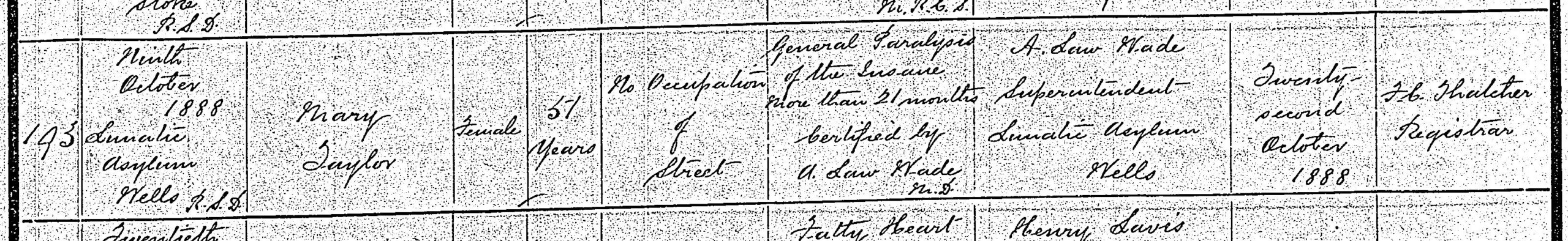

Job heeded the magistrates’ advice about placing Mary in an asylum, as she was admitted to the lunatic asylum at Wells shortly after. She was suffering from tertiary syphilis, probably due to having contracted the disease as a young woman through sexual contact. Since syphilis is only contagious in its early stages, it is likely that Job was not infected. Mary died from the disease on 9 October 1888, at the age of 56.[13]

By April 1891, Job lived in the High Street with three sons and one daughter. Over the following seven years, his children left home one by one until only Ernest was left. Albert married in 1891, Job Junior, enlisted in the Dorset Regiment in 1893,and Mary Annie married on 3 February 1898.

Death

Job died on 25 April 1899, at the age of about 79.[14] Both he and Mary were buried at Street.

Ernest married on 15 April 1900.

References

[1] The will of Abraham Genge, dated 23 September 1830, proved in London on 17 December 1832.

[2] Somerset Heritage Centre, Q/SR/549/22.

[3] England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892

[4] Death certificate of Dinah Taylor; death certificate of Emily Taylor.

[5] Sherborne Mercury 25 August 1857, p.5.

[6] The family lived at Snell’s Buildings near Waterbeer Street, Exeter, in 1841, and at Woodbine Place near Sidwell Street, Exeter, in 1851. Tenison Street no longer exists but was on the south bank, close to Hungerford Railway Bridge and Waterloo Station.

[7] Western Gazette, 10 December 1869, p.4.

[8] Western Gazette, 8 July 1870, p.7; 7 July 1871, p.6.

[9] Birth certificate of Albert Babb Taylor.

[10] Street baptism register; Western Gazette, 19 April 1878, p. 6.

[11] Western Chronicle, 3 December 1886, p.8.

[12] Wells Journal, 11 November 1880, p.8.

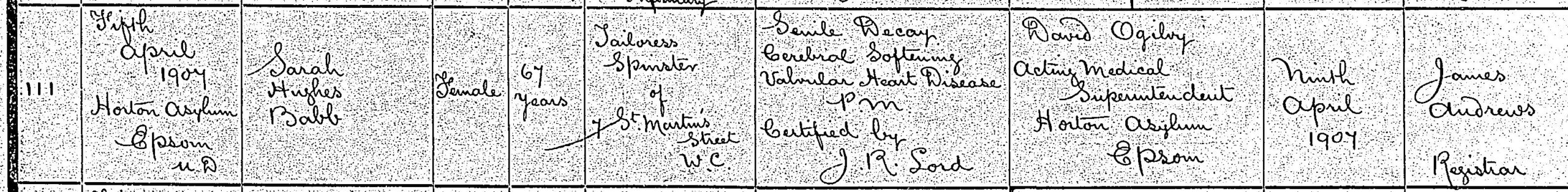

[13] Death certificate of Mary Taylor (age recorded as 51). Her younger sister, Sarah Hughes Babb, died in Horton Asylum, Epsom, on 5 April 1907, but of senile decay, cerebral softening, and valvular heart disease (death certificate).

[14] Wells Journal, 4 May 1899, p.5. This death notice gave his age as 71.