Introduction

This is the story of how the Surrey-born Lillie Louise Jearum became a music teacher and church organist in the small, relatively secluded village of Hardington Mandeville in Somerset. In this modest setting, her musical talents served to enhance the services in the parish church, enrich the lives of her pupils, and generally add to the village’s cultural life. The story commences with her grandfather’s funeral.

Grandfather’s funeral

Just after two o’clock on the afternoon of Monday, 8 November 1897, a funeral cortege, composed of a glass hearse, several carriages and a long line of mourners, left the railway station at Godalming, solemnly proceeding to the parish church. The funeral was for the long-serving station master, Frederick Jearum, who had been a popular and well-respected figure in the town. Among the mourners were Frederick’s son, Ernest, and Ernest’s wife, Lillie Louisa, who had married at the same parish church three years earlier. For that afternoon, Ernest’s and Lillie’s daughter, Lillie Louise, was entrusted to the care of relatives or friends.

Parents’s marriage

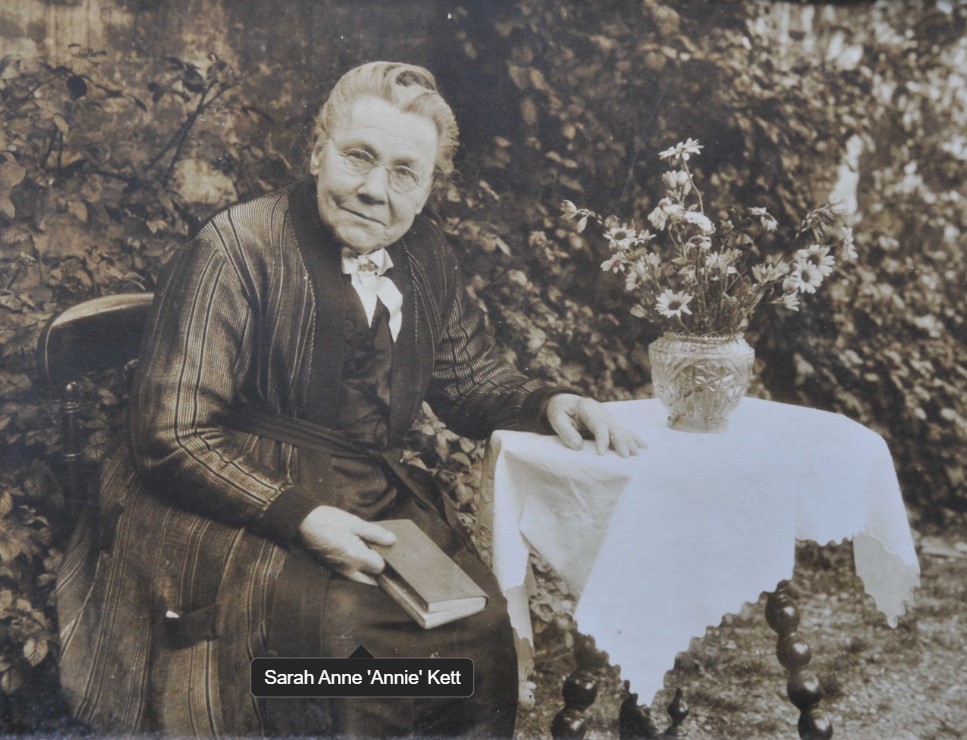

Ernest and Lillie first met when he was a railway clerk at Godalming Station, and she was a cook in a private house in the town. Originally from Hardington Mandeville, in Somerset, Lillie came to Godalming to work for Mrs Martha Vassall, the widow of Hardington’s former rector who died in 1883. After his death, Mrs Vassall relocated to the town to be close to Charterhouse School, which several of her sons attended. Ernest and Lillie married at St Peter and St Paul, Godalming, on 20 March 1894.

Father’s railway career

Ernest Jearum was a railway clerk his entire working life. Starting as a Junior Clerk at North Elms when he was about sixteen, he later held positions at Godalming, Waterloo, Raynes Park, Witley and Haslemere, spending his whole career in London and Surrey, except for the years 1899 to 1903, when he worked in the Railway Telegraph Office at Exeter.[1] While in that city, he and his family lived at 38 Salisbury Road, a red-brick terrace street conveniently close to St James Park Station. After leaving Exeter, Ernest transferred to the Parcels Department at Waterloo.

The interlude in Exeter invites an exploration of whether Ernest’s relocation was voluntary or compelled. Assuming it was voluntary, one might ponder whether the move was an attempt to accommodate Lillie’s desire to return to the West Country or a means for Ernest to evade the obligations of caring for his widowed mother and younger siblings, responsibilities that ultimately fell to his older brothers, Frederick and Charles.

Childhood

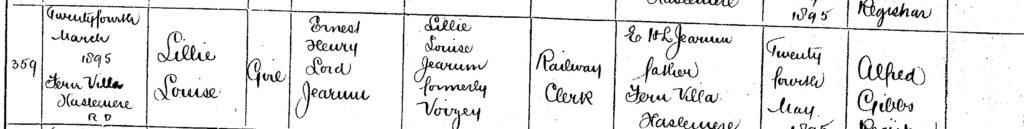

Ernest and Lillie’s only child, Lillie Louise, was born on 24 March 1895 at Fern Villa, Haslemere.[2] However, her earliest memories were probably of Exeter, where she lived between the ages of 4 and 8. Upon their return to London in 1903, the family settled at 11 Edna Road, Raynes Park, remaining there until at least 1915.[3] By 1925, they had moved to 23 Trewince Road, West Wimbledon.[4]

As a single child, Lillie Louise immersed herself in solitary activities that demanded patience, dexterity, and practice. She demonstrated a remarkable talent in knitting and needlework, winning prizes at the Cottenham Park Flower Show in 1909, 1910 and 1911.[5] The shirt she exhibited in 1909 when she was 14 was so admired by some male visitors that they donated money to supplement her prize.

Her true passion, however, lay in piano playing. At the age of 15, she performed a piano solo at a Church concert, and, in 1917, at the age of 22, she passed the Higher Division examinations of the Royal Academy of Music and Royal College of Music.[6] By 1921, she was a music teacher, possibly taking over from her music teacher, Miss Maggie Westbrooke, who ceased advertising for pupils at the end of 1917.[7] Living at home with her parents, Lillie saved much of her income, and in 1924, in the East Chinnock Estate Sale, she bought a cottage and garden of 24 perches at Hillcross, Hardington, which she subsequently advertised as available to let.[8] Whether this acquisition was an investment or a potential retirement haven for her parents remains unknown.

Her father’s employment assured him a steady income, sufficient to fund his daughter’s piano lessons. His salary, which increased by approximately £10 every two to three years, rose from £70 per annum at the time of his marriage in 1894 to £130 at the onset of the First World War, reflecting a real-term increase of 44%. However, wartime inflation eroded the purchasing power of his earnings significantly, such that, in real terms, his salary in 1918 was only 82% of his salary in 1894.[9] Furthermore, the Railways Act of 1921 profoundly impacted his profession, consolidating the country’s 120 railway companies into four large entities, placing Ernest’s employer, the London and South Western Railway Company, under the Southern Railway from 1 January 1923.

These changes would have taken their toll on Ernest’s health, but more crucially, given that his father died at the age of 51, he may have been predisposed to genetic health issues. Ernest died at his home in West Wimbledon on 25 November 1925, aged fifty-four. By his will made one month before he died, he left his small estate of £298 10s 10d to his wife.[10]

Move to Hardington

Following Ernest’s death, his widow and daughter relocated to Hardington, where they could count on the support of Lillie’s siblings—Thomas, Beatrice, Mary Annie, and Blanche—and explore the opportunities- albeit limited- for Lillie (hereafter referred to as “Miss Jearum”) to further her musical ambitions.

Rather than live at Hillcross, mother and daughter lived at Mandeville Terrace, on the church side, and Miss Jearum earned her living as a music teacher and church organist. She played the organ at many funerals, including for notable individuals such as Walter Oxenbury in 1935, Archer Vassall in 1940, and George William Partridge in 1946.[11] She also played the organ at the wedding of Basil and Phyllis Taylor in 1936.[12]

During the Second World War, Miss Jearum took in an evacuee named Barbara South, whom she later fostered. After developing an interest in farming, Barbara attended the Somerset Farm Institute at Cannington, where she met her future husband, Edward Parsons, a farmer from Stathe, near Burrowbridge.[13]

Miss Jearum’s mother died in 1951 at the age of eighty-three. Miss Jearum herself lived to the impressive age of ninety-eight and, in her later years, was cared for by her cousin, Gladys Rawlins.

At some point after 1974, Miss Jearum moved to the house next door, which in its name “Dimple Cottage” memorialises her family nickname.

References

[1] London and South Western Railway Clerical Staff Character Book, No. 4, 1859-1920.

[2] Miss Jearum’s birth certificate. Fern Villa may have been a house in Foundry Road, where her parents lived until 1899 (Voters’ Lists). Foundry Road, renamed King’s Road in 1903, runs west from Haslemere Station, parallel to the railway line.

[3] Voters’ lists.

[4] The will of Ernest Henry Lord Jearum, dated 22 October 1925, proved in London on 30 December 1925.

[5] Wimbledon News, 31 July 1909, p.8; 30 July 1910, p8; 29 July 1911, p.8.

[6] Wimbledon News, 21 January 1911, p.2; 11 August 1917, p.3.

[7] Wimbledon News, 29 December 1917, p.4. Miss Margaret Westwicke is a mysterious figure who, in later life, lied about her age and place of birth. She was born in 1854 (possibly in Liverpool) and practised as a piano teacher in Southampton from 1889 to 1891 before commencing in Wimbledon in 1910. She claimed to have been a pupil of the celebrated pianist Tobias Matthay (1858-1945).

[8] North Devon Herald, 25 September 1924, p.8; Western Gazette, 17 April 1925, p.9.

[9] London and South Western Railway Clerical Staff Character Book, No. 4, 1859-1920.

[10] The will of Ernest Henry Lord Jearum, dated 22 October 1925, proved in London on 30 December 1925.

[11] Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser, 25 December 1935, p.8;

[12] Western Gazette, 2 October 1936, p.15; 13 December 1940, p.3; 2 August 1946, p.2.

[13] Somerset County Herald, 20 July 1957, p.9; 28 May 1960, p.10 and p.12.

I am grateful to Sally Knibbs for information on some points.