Introduction

Samuel John Gillim is remembered as one of the village’s war dead. He endured a turbulent childhood marked by the tragic death of a brother from burns shock when he was eleven, followed by the loss of his father to tuberculosis when he was twelve. After leaving school, he worked as a farm labourer in Englishcombe before returning to Hardington. In July 1915, he enlisted in the army, serving for two years before being killed in action on 27 August 1917. His name is inscribed on the Tyne Cot Memorial in Belgium

Birth

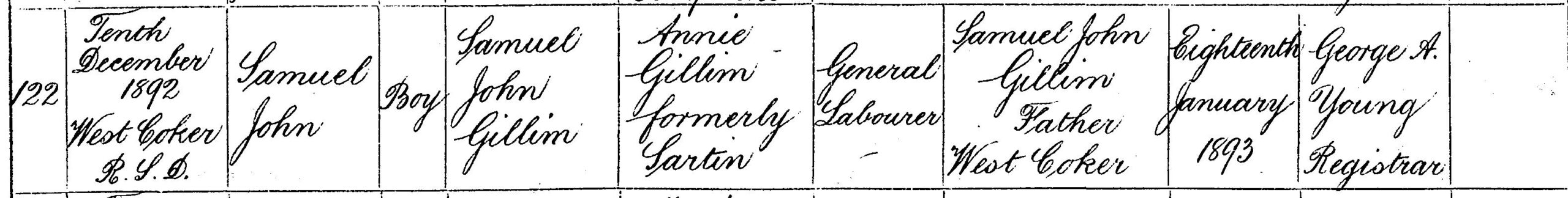

Samuel was born on 10 December 1892 at West Coker, the second of seven children born to Samuel John Gillim and his wife, Annie.[1] His father was a general labourer, while his mother worked as a housemaid in Yeovil before her marriage.

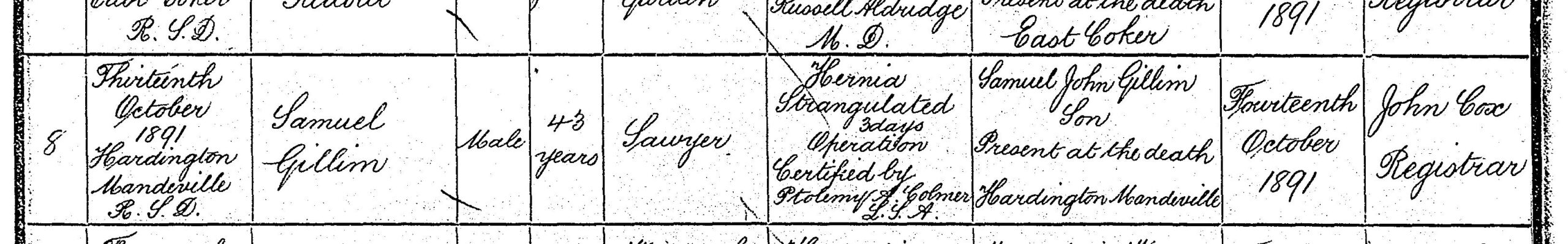

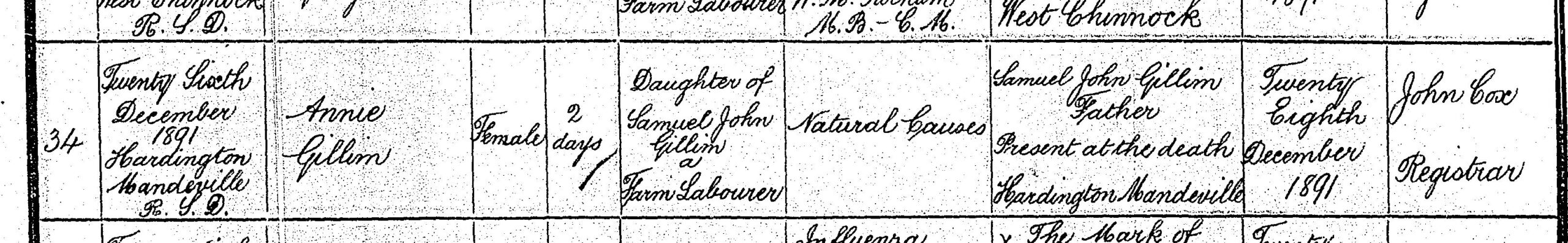

Samuel and Annie were poor and relied on relatives for help. Their early marriage was also marked by grief. They married in about October 1891, while Annie was pregnant with their first child.[2] Samuel was about 19, and Annie was five years older. They probably lived initially at Hardington with Samuel’s parents. However, within about a week of their wedding, Samuel’s father died on 13 October 1891 from a strangulated hernia.[3] Shortly after this tragedy, their first child, Annie, was born at Hardington on 24 December 1891, but sadly died two days later due to “natural causes.”[4]

West Coker

After the death of their first child, Samuel and Annie moved to West Coker, where he continued to work as a labourer. They may have lived with or near Annie’s widowed mother, Fanny Baker, who lived on Coker Hill with four of her children.

Fanny had an eventful life, which significantly influenced her daughter, Annie. Born in Romsey, Hampshire, around 1840, she was the daughter of a farm labourer named George May. In 1867, while still single, she gave birth to her daughter, Mary Ann, who later became known as Annie. Three years later, Fanny married William Adams, a labourer, and together they had three children, though their second child died in infancy. Their relationship ended around 1873, either due to his death or abandonment.

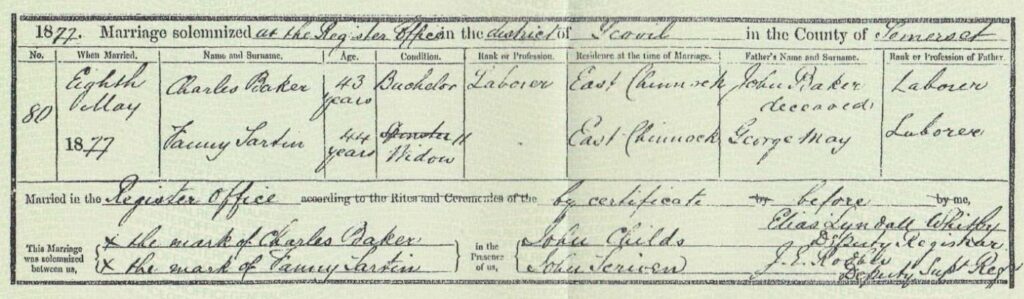

Four years later, Fanny was living in East Chinnock with her three surviving children, identifying as a widow named Mrs. Sartin.[5] On 8 May 1877, she married Charles Baker, a former member of the Royal Horse Artillery, at the Yeovil Registry Office. They lived at East Chinnock and had five children together before Charles died in 1889, after which Fanny moved to Coker Hill, West Coker.

Yeovil

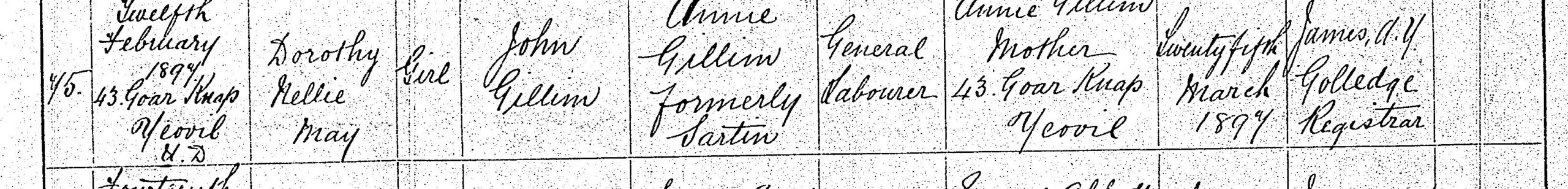

After their time at West Coker, Samuel Gillim Senior and his family moved to Yeovil, where, in 1897, they lived at 43 Goar Knap. While living in Yeovil, they had two more children, Ernest George and Dorothy Nelly May, but unfortunately, Ernest George died in infancy.

Hardington

By 1898, the family had moved to North Lane, Hardington, where they had three more children: William Arthur Charles, Albert Edward and Thomas Pearce.[6] The 1901 census recorded Annie’s half-brother, Charles Baker, living with them.

Move to Melcombe Regis

In about November 1903, Samuel Senior was diagnosed with tuberculosis.[7] Following this diagnosis, the family moved to the Dorset coast. By September 1904, they lived at 15 Ferndale Road, Melcombe Regis, where Samuel Senior worked as a contractor’s carter.[8]

A tragic death

On Monday, 19 September 1904, the day started normally for the family. At 5.30 a.m., Samuel Senior left home to go to his employer, Mr H. P. H. Vincent, at Commercial Road, Weymouth. At about 8.30, Annie went outside to call their son, Samuel Junior, to get ready for school, leaving their seven-year-old daughter, Dorothy, and four-year-old son, Albert, in the kitchen. Annie did not return to the house immediately because she began talking to a neighbour. While she was absent, Albert took hold of a piece of paper, put it in the fire, and then drew it out, setting his shirt ablaze. Dorothy tried to extinguish the fire but was unsuccessful. Panicking, she ran into the street to fetch her mother, and Albert followed her. A passing carter saw the child and quickly tore off the burning clothes and doused the flames. Although the child was taken to the Royal Hospital, the doctors soon realised that his condition was hopeless, and he died the same day.[9]

Poor Dorothy was required to testify at the inquest, recounting how she had tried to put the flames out, but “Albie would not keep still.” The incident almost certainly had a devastating impact on her life, as she never married or held a job. In a tragic twist, she died on 30 June 1942 from injuries sustained during a bombing raid on Weymouth.[10]

At the time of Albert’s tragic death, Samuel Junior was eleven years old and nearing the end of his schooling.[11] Although he did not testify at the inquest, he must have witnessed enough of the incident to suffer trauma.

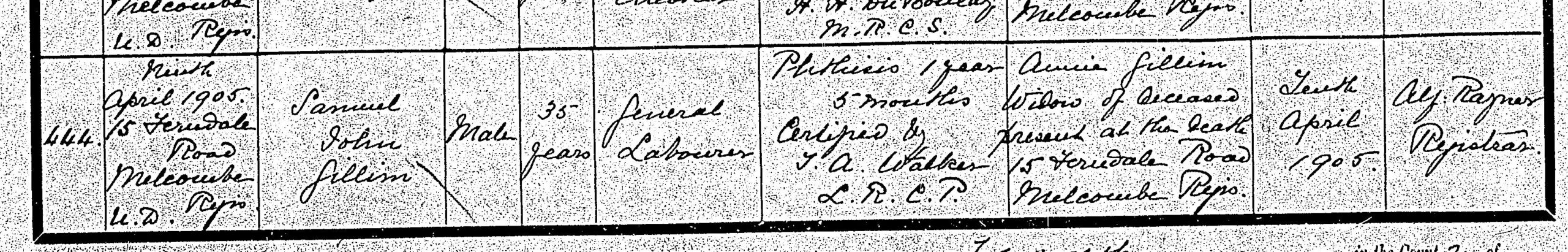

Father’s death

Samuel Senior succumbed to tuberculosis on 9 April 1905 at the age of 35.[12] His widow remained in the Weymouth area and, in 1909, had a son with another man. She named him Albert Edward Towels, to commemorate her son lost to the fire. By April 1911, she was living in a single room at 18 High Street, Weymouth, with her two youngest children, Thomas and Albert.[13] She probably found it difficult to discipline them when they got older, and in June 1915, local magistrates ordered Thomas to attend Milborne St Andrew Industrial School due to his irregular school attendance.[14]

Englishcombe

By April 1911, Samuel Junior had left home and was working as a farm labourer at Englishcombe, near Bath, boarding with a farm carter.[15]

Return to Hardington

In July 1913, Samuel stayed with his uncle, Charles Ernest Gillim, his father’s brother, at Hardington Marsh. At that time, he was charged with behaving indecently towards his cousin, Daisy Florence Gilliam. The arresting officer testified to his good character, and after hearing all the evidence, the magistrates dismissed the case.[16]

Military career

Samuel enlisted in the army at Yeovil on 13 July 1915. He initially served with the Dorset Regiment before being transferred to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.[17] His regimental numbers were 12803 for the Dorset Regiment and 29252 for the Warwickshire Regiment.

He was with the 1st/6th Battalion-Territorial when he was killed in action in Belgium on 27 August 1917 at the age of 24.[18] His name is recorded on the Tyne Cot Memorial.[19]

Samuel’s will

Samuel probably recorded a simple will in his pay book, naming his grandmother, Harriet Woodland, as his sole beneficiary. She received his outstanding pay of £4 9s on 31 December 1917 and his war gratuity of £12 on 29 November 1919.[20] Samuel’s mother received a pension of 5s a week from 6 November 1918.[21]

References

[1] Birth certificate of Samuel John Gillim; family reconstitution.

[2] The third reading of their banns was on 27 September 1891 (Hardington banns book).

[3] Death certificate of Samuel Gillim.

[4] Death certificate of Annie Gillim.

[5] There is no record of a marriage between Fanny Adams and a man named Sartin. The 1871 census lists eleven people named Sartin living at East Chinnock. Among them was Charles Sartin, who ran the Portman Arms. His son, John, passed away on March 15, 1875, at the age of 23. However, this age seems too young for him to have been involved with Fanny Adams.

[6] RG13, piece 2297, folio 44, page 8.

[7] Death certificate of Samuel Charles Gillim.

[8] Southern Times and Dorset County Herald, 24 September 1904, p.4.

[9] Death certificate of Albert Edward Gillim; Southern Times and Dorset County Herald, 24 September 1904, p.4; Western Chronicle, 23 September 1904, p.4.

[10] World War II Civilian Deaths, 1939-1945.

[11] At that time, the official school leaving age was twelve, but children could leave earlier after passing a basic literacy test.

[12] Melcombe Regis burial register. The burial register and the Civil Registration Birth Index record his age as 35, but he was actually 32 at the time of his death.

[13] RG14, piece 12353. Although she was a widow, Annie completed the census schedule by stating that she had six children alive and three who were deceased. However, the available records show that she had five children alive and three who had died.

[14] Southern Times and Dorset County Herald, 17 July 1915, p.4.

[15] RG14, piece 14676.

[16] Western Chronicle, 18 July 1913, p.7.

[17] Soldiers Died in the Great War, 1914-1919.

[18] Soldiers Died in the Great War, 1914-1919.

[19] Find a Grave.

[20] Army Registers of Soldiers’ Effects, 1901-1929.

[21] World War I Pension Ledgers and Index Cards, 1914-1923.