Introduction

Charles Ralph Milligan was a devout and serious-minded clergyman with marked musical gifts. He spent his early life in Ireland, which was then under direct governance from London. After receiving a solid education, he experienced a spiritual conversion that led him to pursue a clerical vocation. However, after four years, his time at a mariner’s mission church took a toll on his health, prompting him to move to England for a fresh start.

During his three years at Hardington, shared with his sister Eva, he had ample opportunity to develop his role as a minister and his identity as a church musician. After leaving during the middle of the war, he spent three years in an inner London parish, where he came under the influence of Rev. John Clayfield Stephens, a staunch evangelical who probably helped systematise his religious ideas.

Charles then moved to Boston, Lincolnshire, to take charge of a chapel of ease. At the age of 38, he returned to Ireland to continue his ministry. His interest in youth work and education led him to serve as the headmaster of a secondary school in Roscrea from 1931 to 1935. He ultimately retired from parish work in 1942.

Childhood

Charles was born in Dublin on 11 May 1882, as the first of eight children born to Andrew and Amelia Milligan.[1] His father worked as a clerk or accountant, and the family lived at 5 Frankfort Place, a respectable middle-class neighbourhood in Upper Rathmines.[2] During this time, Dublin was one of the most church-dominated capitals in Europe, with religious institutions, particularly the Roman Catholic Church, significantly influencing the city’s schools, charities, and public life. The Protestant minority also maintained its networks of grammar schools, choirs, and youth organisations. This background gave Charles an early familiarity with a society in which ecclesiastical structures played a vital role in everyday life.

The Milligan family could afford to provide Charles with a good education. He initially attended St Patrick’s Cathedral Grammar School, where he was the leading solo boy in the choir in 1890.[3] He then became a boarder at Drogheda Grammar School in County Louth, where he excelled academically. In his final term, he won the Form V Governor’s Silver Medal for general merit, as well as special prizes for Scripture and English Composition.[4]

University, conversion and early career

In January 1903, he entered Trinity College Dublin, where he won a catechetical prize in the first-term examinations, suggesting a deep interest in religion.[5] In June 1907, he graduated with a second-class degree at the age of twenty-five.[6]

What he did for the following year is unclear. Perhaps he pursued a commercial role like his father. However, this period was crucial to his spiritual development, as he later asserted that he experienced a personal conversion, which evangelicals viewed as a sign of divine grace.

Shortly afterwards, he resolved to take holy orders, specifically seeking ordination at the hands of Charles Frederick D’Arcy, the Bishop of Ossory, who was known for his evangelical beliefs and idealist philosophy. Charles was ordained as a deacon at St Canice’s Cathedral in Kilkenny, on 10 June 1908 and was licensed to serve as a curate at Abbeyleix, a small town in County Laois.[7] He returned to Kilkenny on 24 February 1910, to be ordained as a priest.[8]

During his four years at Abbeyleix, Charles performed at a concert at Killermogh parish hall, which was presided over by Lord Castletown, the leading landowner in the district.[9] He also travelled to Belfast to speak at a meeting of the Protestant Total Abstinence Union.[10]

Charles’s next curacy was to the Mariners’ Church at Kingstown.[11] The trustees agreed to his appointment on 10 January 1912, and he commenced his duties the following month.[12] In March 1912, his Abbeyleix parishioners presented him with two volumes of music, a communion set, a purse of sovereigns, and an address commending his four years of “unsparing labour to advance the moral and spiritual welfare of the congregation.”[13]

The Mariners’ Church, located near Dublin Bay, had been founded as a mission for seafarers, but its pews were mostly filled with retired naval officers and middle-class families who preferred its lively evangelical services. During his time there, Charles gave a talk to the Men’s Christian Institute and attended a Boys Brigade demonstration at the Town Hall.[14]

After just eight months, Charles resigned for health reasons.[15] His convalescence appears to have taken several months, but he had recovered sufficiently by 9 June 1913 to attend the annual prize distribution at St Columba’s College in Rathfarnham.[16]

By this time, he may have been planning to move to England. There were no institutional barriers to such a move, as the Church of England fully recognised the orders of the Church of Ireland, and Irish priests required only episcopal testimonials and subscription to the Articles to be licensed. Charles decided to accept a position as a curate at Hardington, perhaps drawn by his evangelical principles and his tireless work in promoting temperance.

Hardington

Charles was at Hardington for the Harvest Thanksgiving in September 1913, helping to decorate the church and take the services. He also accompanied Miss Salome Wallace on the organ as she sang a solo.[17]

Through the winter, he continued to make a strong impression on the village. At a meeting at the rectory on 5 December 1913, Cleife formally inaugurated him as choirmaster and told the choir about his exceptional musical ability.[18]

By Christmas, Charles had been joined by his sister, Eva Henrietta, then aged twenty, and together they helped decorate the church with evergreens and other plants. After the Christmas Day evening service, he performed in a sacred concert, again accompanying Miss Wallace and playing an organ solo.[19] During the watchnight service on 31 December, he delivered an eloquent address.[20] When Cleife and his wife hosted church workers at the rectory on 21 January 1914, Charles and Eva were actively involved. Eva helped serve at the tables, and Charles played three pieces from Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words.[21]

At this time, Rev. Charles Godfrey MacCarthy, a former curate, lived in the village and occasionally assisted at the church. On 23 January 1914, he died of “apoplexy” at the age of 66.[22] Charles Milligan assisted Cleife in conducting the funeral.[23]

The cultural high point of Charles’ time at Hardington was probably the concert held in the schoolroom on 16 April 1914. Organised by Francis Purchase, it featured songs, readings and music. Eva recited Longfellow’s poem “The Legend Beautiful”, and she, Mrs Cleife, Charles and Francis sang “Crossing the Bar” set to music composed by Charles.[24]

The following month, Charles chaired a meeting of the village athletic club at the New Inn. It was decided to form a cricket team, and Charles was appointed captain.[25] When they played East Coker in August, Charles scored ten runs.[26]

In June, Charles spoke in church about the parish work of Lily Amelia Voizey, an eighteen-year-old farmer’s daughter who had died tragically while working away from home.[27]

On Friday, 21 August 1914, and Sunday, 30 August 1914, Cleife and Charles conducted intercession services for the country’s military forces engaged in the war.[28] In October, Cleife fell ill and entered a terminal decline, dying on 11 December 1914. Charles assisted with his funeral and preached a sermon in Cleife’s memory the following Sunday.[29]

It took nine months to find Cleife’s replacement, during which time Charles remained at Hardington. In January 1915, he officiated at the funeral of Emma White.[30] In August, he led a memorial service for Henry Baker, who was killed in action.[31] In September 1915, he and Eva participated in a tea at the rectory for the Sunday School children, and Eva came first in the ladies’ race.[32] It was not until 1916 that he left the village.[33]

Eva’s romance

By that time, Eva had probably become romantically involved with Benjamin Emmanuel Frank Mitchell. Born at East Coker in 1890 and the son of a gardener, he became a Captain in the Church Army by the age of twenty. He enlisted in the army on 24 July 1915 and was awarded the Military Cross later that year.[34] He and Eva were married at St Giles, Camberwell, on 10 August 1917.[35] After the war, he took holy orders and served for many years as vicar of St Michael’s, St Albans, ultimately succumbing to a World War I leg wound in 1941.[36] Eva died on 12 April 1973 at the age of 79.[37]

Stoke-sub-Hamdon

During March and April 1916, Charles assisted at Stoke-sub-Hamdon, standing in for the vicar, Rev. G. G. Monck, who was ill.[38]

Paddington

In December 1916, Charles was licensed to the curacy of Christ Church, Harrow Road, in the Paddington district of London, where he served until 1919.[39]

The incumbent, Rev John Clayfield Stephens, probably had a significant influence on Charles’ spiritual development. He was born near Doncaster in 1870, the son of an Inland Revenue Officer, and attended St. John’s College, Cambridge, from 1889 to 1893, earning a BA. In 1899, he studied at Ridley Hall, Cambridge, before taking holy orders the following year. He spent his entire ministry in London, including serving as the incumbent of Harrow Road from 1910 until his death in 1925.[40] He did not marry until 1923, when he was 52.[41]

The voting lists of 1918 show that Charles and another clergyman named James Albert Burnley (1872-1932), were living at 31 Elgin Avenue, the home of a publisher’s secretary and his wife. Like Stephens, Burnley had studied at Ridley Hall.[42]

This connection to Ridley Hall is important because it was an evangelical theological college closely associated with the Keswick or Higher Life movement. This movement promoted a practical, experiential evangelicalism centred on personal consecration, holiness of life and the empowering work of the Holy Spirit.[43] Its core belief held that the Christian life includes two primary turning points: justification (or becoming saved) and sanctification (spiritual cleansing). Clergy from this tradition valued simple, expository preaching and moral seriousness, while being wary of ritualism or ceremonial excess. The values and doctrines of this movement would have appealed to Charles, and someone, probably Stephens, expressed the hope that he would remain loyal to these strong evangelical views in his next parish.[44]

Boston

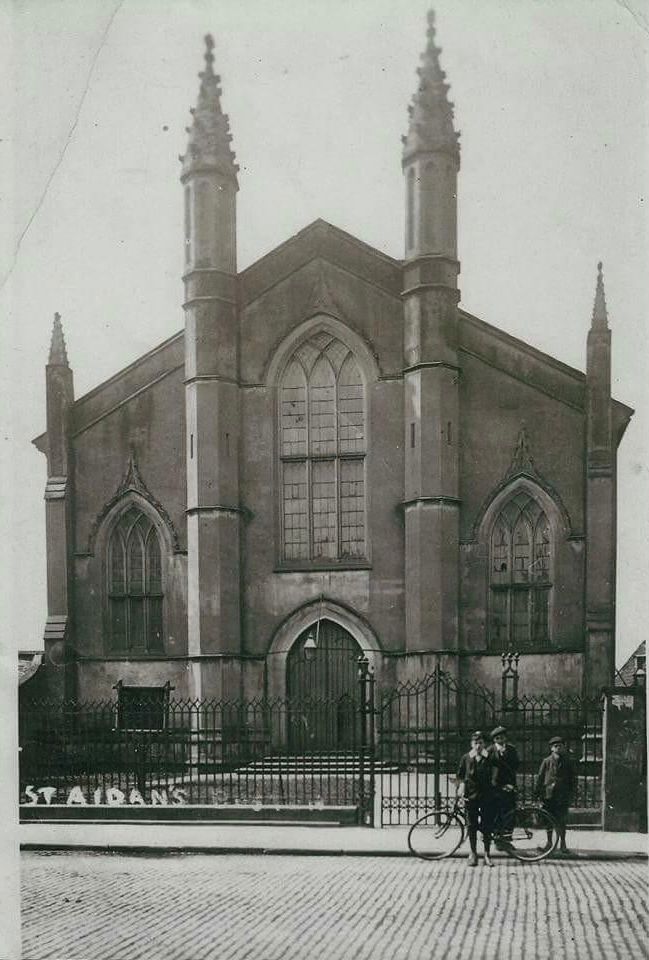

In December 1918, he accepted the incumbency of St Aidan’s, a chapel of Ease in Boston, Lincolnshire, which had been vacant since April 1918.[45] The patron was Bernard Francis Rice, a local solicitor.[46] Charles preached there as the incumbent designate on 22 and 25 December, making a good impression on the congregation.[47] Earlier in the year, he had paid the fee required to convert his bachelor’s degree to a master’s degree, so he took the appointment as Milligan M. A.

A local newspaper described him as kind, sympathetic, and engaging, with a strong, clear voice and considerable musical talent. His faith was “grounded in the doctrines of grace”, and he “expounded the simple Gospel of salvation through faith in the crucified and risen Lord.”[48]

The Bishop formally instituted him at Lincoln on Saturday, 22 February 1919. Charles then returned to Boston for a reception at St John’s Hall, which included a programme of music.[49] The following morning, he went through the ceremony of “reading himself in” and in the evening, delivered a sermon on the parable of the sower. He said that he came amongst them as “simply one who sows the seed.”[50]

His strong evangelical views soon became a matter for comment. He forbade the choir from wearing surplices and instructed them not to turn to the East when the creed was repeated. One of his parishioners remarked that “He ought to be a Chapel minister.”[51]

In July 1919, he returned to Christ Church, Harrow Road, for a sale of work, and in September, he took a short holiday.[52] In October, he joined the committee of the Boston branch of the British and Foreign Bible Society.[53] In December, he sat on the platform at a meeting of the Alliance of Honour, an organisation dedicated to promoting male sexual purity.[54]

In March 1920, it was announced that Charles was leaving Boston for Ireland.[55] He preached his farewell services on 2 May.[56]

Return to Ireland

Charles returned to Ireland during a period of political turmoil that culminated in the establishment of the Irish Free State in December 1922. He served as curate of St Kevin’s, Dublin, between 1920 and 1924, before becoming curate of St Matthias, Dublin, and minister-canon of St Patrick’s Cathedral from 1924 to 1928. He then entered diocesan administration as diocesan curate of the Diocese of Killaloe from 1931.[57]

Soon after his return to Ireland, he became chaplain of the 31st Company of the Boys Brigade. This role involved attending summer camps, and on 14 March 1923, he gave a lantern lecture about one of the camps held near the Glen of Downs in County Wicklow.[58]

Roscrea

In January 1932, he became the headmaster of a newly opened secondary school at Roscrea. A local newspaper noted that he had previously been an assistant master at Hurst Lodge School, Putney, and at Cambridge House School, Margate, although the dates remain unclear.[59] During his time at the school. he undertook a tour of the Norwegian Fjords on the Cunard liner Ansonia, later recounting his experiences to the Roscrea YMCA.[60]

Later ministry

After four years at the school, he left in January 1936 to take charge of the parishes of Templederry and Ballinaclough, receiving a mantelpiece clock as a farewell present.[61]

In 1938, he became the curate-in-charge at Dunlavin, where he was elevated to rector in June 1940.[62] He retired in 1942.[63]

Charles died at Glebe House, Glenealy, County Wicklow, on 24 June 1948 at the age of 66. He was buried beside his father at Mount Jerome in Dublin.[64]

He left a widow, Alice Jessica, whom he married in 1941. As he was married when he left Roscrea School, he must have been married twice, though the name of his first wife is unknown.[65]

References

[1] Rathmines baptism register.

[2] Rathmines baptism register; censuses of 1901 and 1911.

[3] Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 1 March 1919, p.3.

[4] Drogheda Conservative, 16 December 1899, p.8.

[5] Boston Gurdian, 1 March 1919, p.3.

[6] Dublin Daily Express, 29 June 1907, p.2.

[7] Kilkenny Moderator, 13 June 1908, p.5.

[8] Lame Times, 12 March 1910, p.7.

[9] Kilkenny Moderator, 5 March 1910, p.7.

[10] Belfast News, 11 May 1911, p.5.

[11] Irish Independent, 12 January 1912, p.3.

[12] Dublin Daily Express, 13 January 1912, p.8; 28 September 1912, p.8.

[13] Midland Counties Advertiser, 14 March 1912, p.2.

[14] Dublin Daily Express, 16 March 1912, p.7; Evening Irish Times, 30 May 1912, p.5.

[15] Dublin Daily Express, 28 September 1912, p.8.

[16] Warder and Dublin Weekly Mail, 14 June 1913, p.5.

[17] Western Chronicle, 26 September 1913, p. 5.

[18] Western Chronicle, 12 December 1913, p. 7.

[19] Western Chronicle, 2 January 1914, p. 6.

[20] Western Chronicle, 9 January 1914, p.6.

[21] Western Gazette, 23 January 1914, p. 5.

[22] Death certificate of Charles Godfrey MacCarthy.

[23] Western Chronicle, 6 February 1914, p. 6.

[24] Western Chronicle, 24 April 1914, p. 6.

[25] Western Chronicle, 22 May 1914, p.5.

[26] Western Chronicle, 14 August 1914, p.3.

[27] Western Chronicle, 3 July 1914, p.4.

[28] Western Chronicle, 4 September 1914, p. 6.

[29] Western Chronicle, 18 December 1914, p. 3; 1 January 1915, p. 6.

[30] Western Chronicle, 29 January 1915, p.5.

[31] Western Chronicle, 3 September 1915, p.8.

[32] Western Chronicle, 3 September 1915, p.6.

[33] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1932, p. 897.

[34] British Army World War I Medal Rolls Index Cards, 1914-1920; Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1932, p. 901.

[35] St Giles, Camberwell, marriage register.

[36] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1932, p. 901; Chelmsford Chronicle, 21 March 1941, p.6.

[37] National probate index; civil registration death index.

[38] Western Chronicle, 18 February 1916, p.5; Western Chronicle, 10 March 1916, p.2; Western Gazette, 21 April 1916, p.10; Western Chronicle, 28 April 1916, p.5.

[39] Morning Post, 15 December 1916, p.8; Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1932, p. 897.

[40] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1908, p.1356; Bayswater Chronicle, 12 February 1910, p.8; 2 May 1925, p.6.

[41] Bromley & West Kent Mercury, 13 April 1923, p.3.

[42] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1932, p.182. Burnley married in 1904 and had one daughter. He was the chaplain of Holborn Workhouse from 1908 to 1914. He was then appointed rector of Chastleton in the Cotswolds.

[43] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1908, p.1356.

[44] Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 29 March 1919, p.9.

[45] Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 7 December 1918, p. 5; 1 March 1919, p.3.

[46] Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 25 February 1919, p.10.

[47] Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 28 December 1918, p.8.

[48] Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 11 January 1919, p.5.

[49] Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 22 February 1919, p.5.

[50] 1919, p.3.

[51] Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 29 March 1919, p.9.

[52] Bayswater Chronicle, 5 July 1919, p.5; Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 27 September 1915, p.7.

[53] Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 18 October 1919, p.12.

[54] Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 13 December 1919, p.10.

[55] Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 27 March 1920, p.7.

[56] Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 2 May 1920, p.7.

[57] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1932, p. 897.

[58] Warder and Dublin Weekly Mail, 24 March 1923, p.3.

[59] Northern Whig, 22 December 1931, p.11.

[60] Midland Counties Advertiser, 27 October 1932, p.5.

[61] Midland Counties Advertiser, 9 January 1936, p.6.

[62] Leinster Leader, 29 June 1940, p.2.

[63] Irish Independent, 26 June 1948, p.3.

[64] Irish Independent, 3 July 1948, p.3.

[65] The Irish civil registration marriage indexes suggest his first marriage was in 1928.