Introduction

Walter Sprague worked as a platelayer on the railway line between Pendomer and Hardington from at least 1911 to 1921. His life was shaped by several significant events: the early death of his father, his sister’s marriage, his own marriage to a Prussian-born woman, and his long railway career. After moving to North Devon in the 1920s, he tragically lost his life in an accident.

Childhood

Walter was born at Shute in about 1882, the fifth of six children born to Tom and Charlotte Ann Sprague. His father was a railway platelayer, while his mother was the daughter of a cooper.

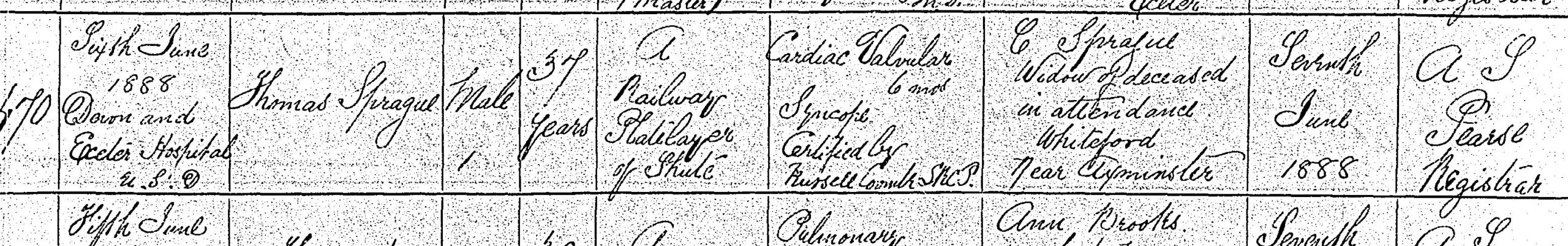

When Walter was five, his father became ill with heart valve disease. He was admitted to Exeter Hospital but died on 6 June 1888 at the young age of 39.[1]

His death plunged the family into crisis, as all the children were still minors.[2] The two daughters, Eliza and Sarah, left home to work as domestic servants, while Robert, the oldest son, became a milkman at Seaton before enlisting in the 20th Hussars in 1892. The three youngest children—George, Walter, and William—remained at home with their mother, likely attending the village school between the ages of five and eleven.

Move to Bournemouth

In his teens, Walter worked as a greengrocer’s assistant at Moordown near Bournemouth. He and his brother, William, lodged with their sister, Eliza, who married William James Snell, the Verger of St John’s Church in Moordown, in 1896.[3]

Marriage

By his early twenties, Walter had returned to Shute and, like his brother George, found work as a railway platelayer. After his return, he met Martha Emma Johanna Wenzel, a barmaid at the Refreshment Rooms in Queen Street, Exeter.

Martha’s background was unusual. She was born in Breslau, then part of Prussia, in 1865, and came to England as a child with her parents and two sisters. Her father worked as a boot and shoemaker in Southwark and Lewisham until his death in 1901. Her sisters, Beda and Gertrude, both married men from the West Country who had moved to London. Martha may have joined the pub trade through her brother-in-law, Ernest Kent, a public house manager originally from Plymouth. The 1901 census recorded her age as thirty, although she was actually thirty-five.

How Walter and Martha first met is unclear. Shute lies twenty-five miles from Exeter, and it is possible that Walter encountered her through the railway connection — the Queen Street refreshment rooms were owned by the London and South Western Railway — or perhaps on a Saturday evening visit to the city. Despite their cultural differences and a seventeen-year age gap, the couple began courting and married at Shute on Christmas Eve in 1906. For Martha, this marriage was a significant transition as she moved from being a barmaid to becoming a wife, and from city living to rural life.

Hardington and Pendomer

After their marriage, Walter continued his work as a platelayer. By April 1911, the couple lived in a railway cottage at Kit Hill, Pendomer, and by June 1921, they had moved to a railway cottage at Hardington Marsh. The exact timing of their move is uncertain, but they were living in one of these places during the First World War. Martha’s Prussian origins may have attracted suspicion during wartime, although no records survive to indicate how their neighbours viewed her.

Chulmleigh

Later, Walter transferred to the Barnstaple Branch, working as a foreman on the Colleton Mill length.[4] By 1931, he and Martha lived at 1, the Railway Cottages, Colleton Mill, Chulmleigh.

On 31 March 1931, he was struck by a train near South Molton Road Station, suffering a fractured arm and four broken ribs. He was taken to North Devon Infirmary, where he died of pneumonia five days later. At the inquest, a house surgeon testified that Walter admitted he had heard the train coming but had misjudged its speed. The jury returned a verdict of accidental death, exonerating the engine driver from any blame.[5] Walter’s funeral was a quiet affair, attended by his wife Martha, his sister Sarah Bates, and his half-sister Emily Dayton, with six platelayers acting as bearers.[6]

Martha’s later life

Walter’s death left Martha, then in her mid-sixties, dependent on family support. She engaged an Exeter solicitor to make her will, leaving her estate to Sarah Bates or, failing that, to Sarah’s son William. [7] She moved to Eastleigh, Hampshire, where Sarah was living at the time, and remained there even after Sarah returned to Devon. Walter’s brother William also lived in Eastleigh, thus maintaining family connections.

By September 1939, Martha was living at 260 Southampton Road with another widow. She later moved ten miles east to Bishops Waltham and eventually entered a council-funded care home called the Gardens at Romsey. Martha died there on 16 August 1943, at the age of 78, leaving an estate valued at £132 15s 2d. Although initial letters of administration were granted to the Treasury Solicitor, her will was later found, and probate was confirmed to Sarah Bates.[8]

References

[1] Death certificate of Thomas Sprague.

[2] Charlotte also had an illegitimate daughter, Emily Louisa Harding, who left home before April 1881.

[3] Bournemouth Graphic, 10 March 1911, p.5. William James Snell was born at Ottery St Mary in about 1871 and became the Verger of St John’s in 1888.

[4] North Devon Journal, 16 April 1931, p.5.

[5] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 9 April 1931, p.8; Western Times, 10 April 1931, p.16.

[6] North Devon Herald, 16 April 1931. The report refers to Walter’s “sisters” without naming them. As Eliza died in 1926, the report, if accurate, must refer to Sarah and Emily.

[7] The will of Martha Emma Johanna Sprague, dated 23 April 1931, proved at Llandudno on 24 April 1944.

[8] The will of Martha Emma Johanna Sprague, dated 23 April 1931, proved at Llandudno on 24 April 1944; national probate calendar.