Introduction

William John Beck Hancock served as a curate at Hardington from 1909 to 1910. The appointment was temporary, and, in this respect, typical of a clerical career characterised by movement between parishes. Although he came from a relatively prosperous family, possessed musical and social talents, and appeared to have been well-liked by parishioners, he never secured a benefice of his own. While it is tempting to attribute his mobility to personal preference, this explanation feels insufficient given that he spent fourteen years in one parish and nine in another. It is more likely that a combination of limited patronage, his temperament, and other circumstances worked against him.

Childhood

William was born at Brompton on 24 February 1853, probably at 2 Alexander Square, near the site of the Victoria and Albert Museum.[1] His father, Thomas, ran a workshop making ladies’ shoes and employed 20 workers.[2] His mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of Charles Beck, a soldier who served in the 57th Regiment of Foot.[3]

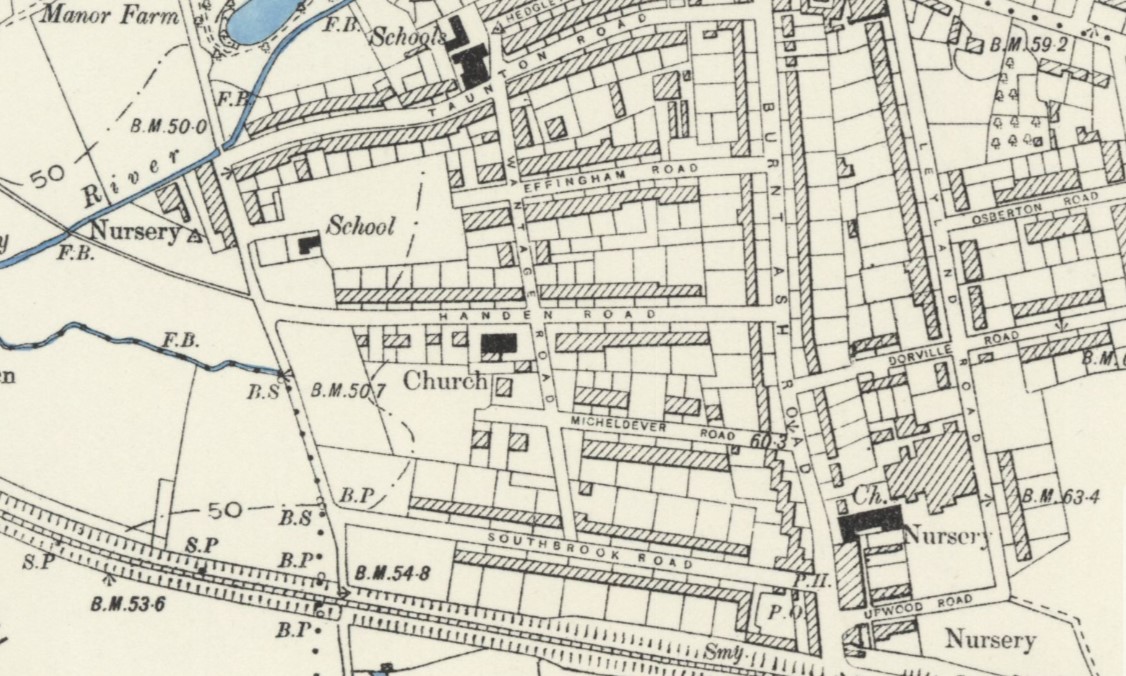

In the late 1850s, the family moved from central London to Charlton, located between Greenwich and Woolwich. By January 1859, they were living at 5 Inkerman Terrace and by August 1860, they had moved to 2 Wellington Road.[4] By November 1864, the family resided at Alexandra Villa, Eltham.[5]

Thomas was able to provide his sons with a private education. The 1861 census recorded William and his younger brother, George, attending Vale House School, Ramsgate.[6]

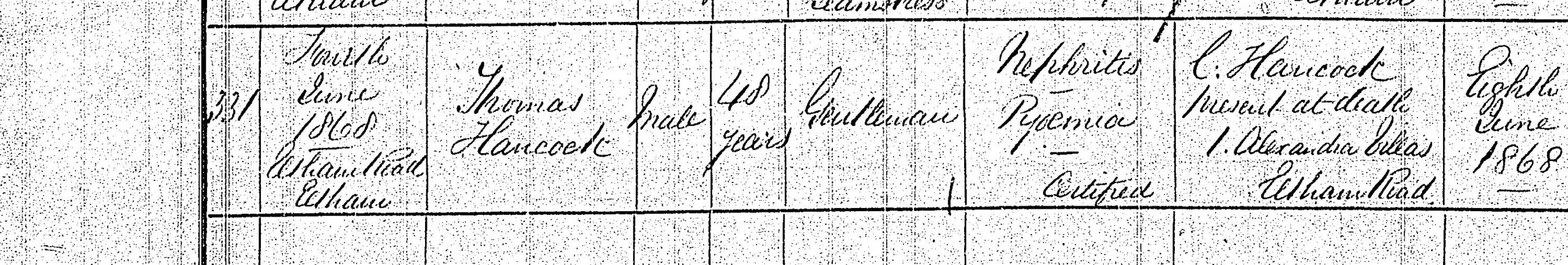

On 4 June 1868, Thomas died at home from nephritis and pyaemia at the age of 48.[7] He left an estate valued “under £7,000,” mostly bequeathed to Elizabeth, who was left to care for their twelve children, including fifteen-year-old William.[8]

After Thomas’s death, the family moved to Woodlands, 39 Burnt Ash Road, Lee, where Elizabeth lived for the rest of her life.

Theological training and ordination

After leaving school, William worked as a tutor from home.[9] In 1879, he began training for a career in the Church of England, becoming an associate of the theological department at King’s College, London.[10] On 28 September 1879, he was ordained as a deacon at Louth parish church in the diocese of Lincoln by Bishop Christopher Wordsworth, a conservative High Churchman of the older, pre-Tractarian school.[11]

Sutton Bridge, Lincolnshire (1879-1880)

William’s first curacy was at St Matthew’s, Sutton Bridge, where he assisted Rev Thomas Drake Young, who had held the living since 1844.[12] Ordinarily, a curate would remain two years, but Young died in July 1880.[13] His successor, Rev Henry Thomas Fountaine, was a younger man who did not require a curate’s assistance, and so William was required to leave.[14]

Threekingham, Lincolnshire (1880-1881)

William then served at Threekingham, a benefice recently augmented by the Poor Benefice Augmentation Association.[15] He boarded at the vicarage with Rev. Frederick Hammond, who had been suffering from poor health since his induction in 1878.[16] Newspaper reports show William reading a story at the choir tea, preaching at the Old Sick Club anniversary, and helping at Harvest Thanksgiving.[17] He was ordained a priest at Lincoln Cathedral on 12 June 1881.[18]

Litcham, Norfolk (1881-84)

In late 1881, William became the curate of Litcham, a large village situated between Norwich and King’s Lynn, where the rector, Rev George William Winter, MA, lived in a spacious rectory with extensive grounds.[19]

William led a pleasant life there, attending friendly society club days, playing cricket and performing in local concerts.[20] He also used his position to help a young man secure a tutoring position by placing advertisements in the Norwich Mercury in March 1883.[21] This may have been for a parishioner or one of his brothers.

William left Litcham in 1884 and was succeeded by Rev Charles William Heald, MA of Corpus Christi College, Oxford.[22]

Great Waltham, Essex (1884-86)

By June 1884, William was curate of Great Waltham, Essex, under Rev Henry Edward Hulton, MA of Trinity College, Oxford.[23][24] Hulton, born in Preston, Lancashire, in 1839, was a lifelong bachelor who left an estate valued at almost £60,000 upon his death in 1922.[25]

William’s life at Great Waltham resembled his previous experiences at Litcham. He played cricket, attended choral festivals in Chelmsford and visited Little Waltham for the reopening of the church and the installation of a new organ.[26]

In October 1885, he placed another advertisement, this time recommending a fifteen-year-old lad for domestic service. [27] Possibly, he felt particular sympathy for the boy because he was the same age as William when he lost his father.

The reasons for William’s departure from Great Waltham are unclear. He was succeeded by the recently married Rev Philip Morgan, who served from 1886 to 1890.[28]

Bracknell, Berkshire (1886)

In about May 1886, William was appointed as a curate at Bracknell to assist the ailing Rev Charles Pallmer Tidd-Pratt, MA, who died in August 1886.[29] William preached his farewell sermon on 19 December 1886, prior to the induction of a new rector.[30] Three weeks earlier, he presented a paper on “Free Education” at the local reading room, arguing for the continuation of school fees for all pupils except paupers and warning that abolishing them would damage voluntary schools and unfairly increase the burden on ratepayers.[31]

Tingewick, Buckinghamshire (1887-1901)

William’s next move to Tingewick brought him stability at last. He served for fourteen years under the elderly rector, Rev. John Coker, becoming deeply embedded in village life.[32] Tingewick was an agricultural parish of around 800 inhabitants, with a lively culture that included friendly societies, concerts, sports, and reading-room activities.

His life in Tingewick tended to follow an annual cycle, with 1895 serving as a typical example. In January, he attended a confirmation service; in February, he took part in the yearly choir supper; and in March, he chaired a meeting of the cricket club, at which he was re-elected as vice-president and treasurer.[33] In April, he attended a meeting of the trustees of the Poor Plot and was elected chairman of the technical education committee.[34] In May, he wrote a letter to the parish council suggesting improvements to the cemetery chapel and attended the annual Sunday School prize giving.[35] In June, he participated in the Club Days of the village’s two friendly societies, while in July and August, he played cricket for Tingewick.[36] In September, he drove over to Shelswell Park for a Sunday School treat and chaired a cricket club tea at the Old Schoolroom.[37] In October, he was re-elected as a vice-president of the reading room, and in December, he sang a song at the Old People’s Supper and attended the school children’s Christmas tea.[38] Over the course of the year, he also helped run the clothing club, established in 1894.[39]

Additionally, he travelled to Buckingham for several events, including the archdeacon’s visitation in April, a meeting of the district technical education committee in May, and a meeting of the juvenile branch of the British and Foreign Society, also in May.[40]

When an exhibition about the village’s history was held in 1887, William chaired the working committee, delivered a lecture on the parish registers, and climbed the tower to record the inscriptions on the bells.[41]

In addition to possessing the skills required for all these activities, he sang in concerts, delivered extempore sermons, and mingled with the local gentry at yeomanry reviews, concerts, and garden parties.[42]

Despite these talents, William had no job security. When Rev Coker died on 31 July 1901 at the age of 80, William knew that he would soon have to leave.[43] However, many felt that his loyal service should be rewarded. When it was announced in November that Rev Harry Boughey Walton, MA, had accepted the living and would begin his duties in January 1902, someone wrote to the Buckingham Express to say that there were “people who would be glad to know if the curate of the parish is likely to be appointed to a living as a suitable and well merited recognition of 14 years zealous and indefatigable labour.”[44]

In his farewell sermon on 1 December 1901, William chose a passage from Isaiah to speak about the majesty of Christ and the joy of those who accepted him. He concluded by wishing that God would bless them both temporally and spiritually. That evening, about thirty past and current Sunday School teachers gathered in the Old Schoolroom to present him with an inkstand, a pair of candlesticks, a glazed frame and a photograph of the church. Moved by the occasion, William thanked them for the gifts and acknowledged the moral and spiritual value of their work.[45]

His parishioners were sad to see him leave. After he left, a committee was formed to buy him a gift, and they invited him back to Tingewick one last time on 17 February. The Old Schoolroom was filled to capacity to see him presented with a dressing case. In a warm and eloquent acceptance speech, he thanked them for their gift and shared his belief in being active and doing one’s duty.[46]

Great Bourton, Oxfordshire (1902-1904)

William next became curate of Great Bourton, a smaller and less culturally active parish. He assisted Rev Alfred Highton, who was in his early seventies and nearing the end of his thirty-year term as vicar.[47] William’s duties began on the first Sunday in 1902 and continued until about April 1904.[48]

In his first year, he helped organise coronation celebrations, participated in a ruri-decanal meeting that discussed the coronation, attended a choral festival at Adderbury, and accompanied Sunday School teachers on a summer excursion to Edgcote House.[49] In his second year, he attended a service marking the fiftieth anniversary of St James’s Church, Clifton, read a lesson at the reopening of Shotteswell Church, attended an open-air concert and garden party at Wood Green, and participated in a ruri-decanal conference at Banbury Town Hall, where he spoke in favour of improving the quality of Sunday School teaching.[50]

William maintained his interest in sports, particularly cricket. He chaired a meeting of the cricket club in March 1902, supported the vicar at a cricket club supper in June 1903, and presided over a meeting of the reading room and athletic club on 19 April 1904.[51]

He also witnessed the destruction and sorrow caused by fire. In August 1902, William assisted at the funeral of a young woman who died when her clothes caught fire while she was cooking.[52] In June 1903, he preached a powerful sermon appealing for donations to help the victims of a fire that had destroyed five labourers’ cottages in the village.[53]

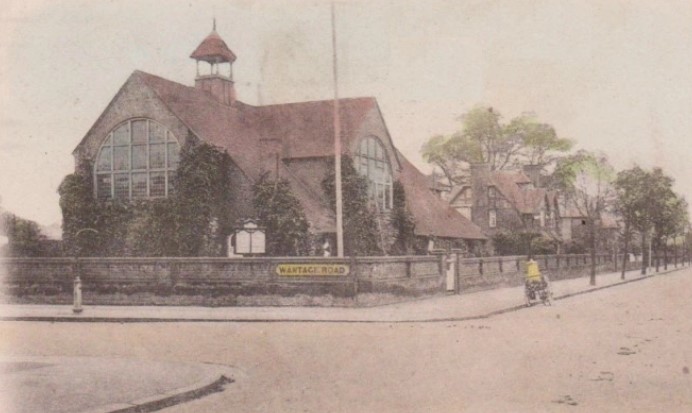

William’s departure from Great Bourton may have been prompted by his mother’s death on 19 April 1904. Her funeral took place on 25 April 1904 at the Church of the Good Shepherd in Handen Road, a church she had attended since its opening in 1881, with burial at Charlton Cemetery.[54] She left an estate valued at £14,458 2s 5d (equivalent to more than £2 million in 2025), which, aside from various bequests of jewellery and small legacies, she divided equally between her ten children.[55] As a result, William inherited about £1,400.

Hardingham, Norfolk (1904-05)

In September 1904, William was licensed to the curacy of Hardingham in Norfolk, where he assisted Rev Charles Stuteville Isaacson, a prolific writer of church history.[56] He remained there until 1905, possibly leaving due to the church’s reroofing.[57]

Terrington St Clement, Norfolk (1906)

In April 1906, William was licensed to the curacy of Terrington St Clement in Norfolk, where he assisted the vicar, Rev Marlborough Crosse, who was then 79 years of age.

Orcheston, Wiltshire (1907)

In 1907, William served as a curate at Orcheston, Wiltshire, assisting the rector, Rev George Thomas Piper Streeter, who was in his mid-seventies.[58]

Ampthill, Bedfordshire (1908)

In the summer of 1908, he provided temporary cover for Rev John George Scrymsour Nichol of Ampthill, who had been in poor health for several years and who was away at Hunstanton.[59] He mingled with the local gentry, attending a missionary festival at Flitwick Vicarage on 30 June and a garden party at Clophill Rectory on 12 August.[60]

Hardington Mandeville, Somerset (1909-10)

In 1909, he became a curate at Hardington Mandeville. In June 1909, he took the Sunday service before Club Day, chaired the Club Day dinner, and attended a choir festival at Martock.[61] His appointment as curate was officially announced in late July 1909.[62] On Sunday, 6 February 1910, he preached a sermon to raise money for the victims of the Paris flood, and on the evening of Tuesday, 22 March 1910, he attended a confirmation service at Holy Trinity Church, Yeovil.[63] Later that month, he helped Cleife with the Easter Day services.[64] One of his final duties at Hardington was accompanying Cleife to the Bishop’s triennial visitation at St John’s Church, Yeovil, on 13 April 1910.[65]

Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire (1910-11)

After leaving Hardington, he became a curate in the town of Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, serving at Holy Trinity under Rev. Henry Travis Boultbee until late 1911. The 1911 census recorded him lodging in two rooms at 9 Rosemount Road. Little is known about his time in the parish except that he attended the speech day at Denstone College on 4 October 1911.[66]

Titchmarsh, Northamptonshire (1912)

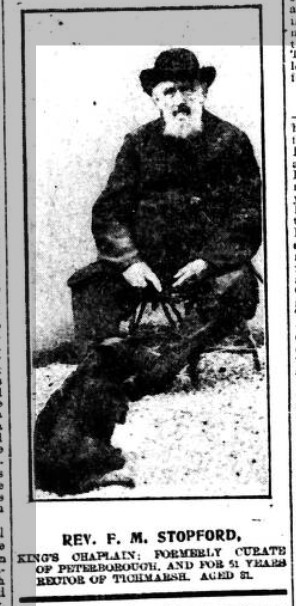

In January 1912, William became the curate at Titchmarsh, assisting the eighty-year-old Rev Frederick Manners Stopford, who had been the rector since 1861 and the Honorary Chaplain to the King since 1901.[67] After Stopford’s death on 24 February 1912, William assisted at the funeral and stayed on as the curate-in-charge until the new rector was inducted in August 1912.[68]

Just before Stopford’s death, William attended a Conservative Party gathering at the Titchmarsh Club Room, which indicates his political affiliation.[69]

Lyddington, Rutland (1912-21)

From 1912 to 1921, William served as a curate at Lyddington, Rutland, working under the vicar, Rev Spencer Richards Pocock, who had been the incumbent since 1900.[70]

Pocock’s career provides an instructive comparison to William’s. Both men came from comparable backgrounds—Pocock being the son of a London solicitor—both trained in theology at King’s College London, and both were regarded as genial, energetic and popular.[71] Yet while Pocock was six years younger and ordained around the same age, he secured his own parish by the age of forty-one. One significant difference between them is that Pocock served as a curate at St Mark’s, Peterborough, from 1893 to 1900, which placed him in plain view of the Bishop of Peterborough, who was the patron of Lyddington.[72] Another is that Pocock married in 1893, which aligned him with the domestic ideal that the Church of England preferred in its incumbents.

Lyddington was a small farming community with a population of 366 in 1901.[73] Although William lived there for nine years, newspapers provide only a few glimpses into his life in the village. He presided over a concert in September 1912, conducted the annual flower service on August 13, 1916 (the flowers from which were sent to the Auxiliary Military Hospital at Uppingham), and on August 6, 1917, he participated in the Rutland Volunteer fete at Oakham, where he won a live pig in a raffle.[74] In October 1920, he took part in the harvest thanksgiving services with the new vicar, Rev Henry Brooke Brown, and in May 1921, he concluded his ministry at Lyddington.[75]

Final years

When William left Lyddington, he was 67 and probably only interested in short-term appointments. He served for three weeks at Bisbrooke, located two miles north of Lyddington, covering for the vicar, Rev Joseph James Wilson, whose wife had died of influenza on 25 April 1921.[76] By June 1921, he was a locum tenens at Geddington, Northamptonshire, living at the vicarage and standing in for Rev Benjamin Turton, who was on holiday with his wife at Whitby.

William lived for a time at Huntly Grove, Peterborough, before entering Heworth Moor House, Heworth, a nursing home near York, where he died on 17 March 1928 at the age of 75.[77] He died intestate, leaving an estate valued at £3,697 11s 5d, which was administered by his brothers, Henry and Arthur.[78]

Conclusion

Hancock’s life exemplifies the precariousness of serving as a curate in the late Victorian and Edwardian Church. Despite being energetic, sociable, musical, and evidently popular, he struggled to gain preferment. While the reasons for this remain unclear, it is possible that his commitment to a life of service and duty left him unusually pliable to circumstance, which may have hindered his personal advancement.

Referernces

[1] Civil registration birth index; baptism register of St Luke, Chelsea.

[2] HO107, piece 1469, folio 280, page 28.

[3] Royal Hospital Chelsea Admission Books, Registers and Papers, 1702-1980; Tunbridge Wells Weekly Express. 14 March 1871, p.2.

[4] Baptism register of Saint Mary Magdalene, Woolwich.

[5] Baptism register of Saint Mary Magdalene, Woolwich.

[6] RG 9, piece 537, folio 95, page 18.

[7] Morning Post, 9 June 1868, p.8; death certificate of Thomas Hancock. He probably suffered from a long, weakening kidney disease with systemic infection (septicemia) developing shortly before death.

[8] The will of Thomas Hancock, dated 30 May 1868, proved at the Principal Registry on 10 July 1868. He left his mother an annuity of £60 and his sister £125, payable after his mother’s death.

[9] RG9, piece 537, folio 95, page 18; RG10, piece 765, folio 135, page 27.

[10] The Calendar of King’s College London for 1895/96.

[11] Stamford Mercury, 3 October 1879, p.5; The Graphic, 28 March 1885, p.2.

[12] Stamford Mercury, 3 October 1879, p.5; Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1874, p. 982.

[13] Pall Mall Gazette, 6 July 1880, p.5.

[14] Lynn Advertiser, 21 August 1880, p.7.

[15] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1885, p. 524; Stamford Mercury, 23 April 1880, p.4

[16] Hull Packet, 15 November 1878, p.2; Grantham Journal, 14 December 1878, p.2.

[17] Grantham Journal, 19 February 1881, p.2; Sleaford Gazette, 28 May 1881, p.4; Grantham Journal, 15 October 1881, p.2. He read “The ghost that ran away with the organist,” a story available by post from Thomas Lloyd Fowler of Winchester.

[18] Stamford Mercury, 17 June 1881, p.5.

[19] History, Gazetteer, & Directory of Norfolk, 1883, p.399-400. The 1911 census recorded the rectory as having 19 rooms.

[20] Lowestoft Journal, 10 June 1882 p.6; Norwich Mercury, 5 July 1882 p.2; Norfolk Chronicle, 15 July 1882 p.10; Norwich Mercury, 15 July 1882 p.6; Norwich Mercury, 9 December 1882 p.7; Norwich Mercury, 26 May 1883 p.7; Thetford & Watton Times, 21 July 1883 p.5; Downham Market Gazette, 22 December 1883 p.5

[21] Norwich Mercury, 3 March 1883, p.4; 10 March 1883, p.1.

[22] Globe, 29 May 1884, p.7; Oxford University Alumni, 1500-1886.

[23] Chelmsford Chronicle, 20 June 1884, p.6.

[24] Kelly’s Directory of Essex,1882, pp.309-10; Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1908, p.729.

[25] National Probate Calendar.

[26] Chelmsford Chronicle, 20 June 1884, p.6;17 October 1884, p.5; 9 October 1885, p.5; Essex Weekly News, 26 June 1885, p.2

[27] Christian World, 8 October 1885, p.19.

[28] Crockfords Clerical Directory, 1898, p.957. Philip Morgan married Emily Florence Kidney at Leytonstone on 3 December 1885 (Leytonstone Express and Independent, 19 December 1885, p.5).

[29] Reading Mercury, 28 August 1886, p.5 (William is referred to as Rev T. Hancock); National Probate Register.

[30] Reading Mercury, 24 December 1886, p.5.

[31] Reading Mercury, 11 December 1886, p.4.

[32] Bucks Herald, 3 August 1901, p.2.

[33] Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 26 January 1895, p.5; 16 February 1895, p.6; 23 March 1895, p.5.

[34] Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 6 April 1895, p.8; 4 May 1895, p.8.

[35] Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 8 May 1895, p.2; 25 May 1895, p.2.

[36] Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 8 June 1895, p.7; 20 July 1895, p.5; 24 August 1895, p.5.

[37] Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press21 September 1895, p.5; 28 September 1895, p.5.

[38] Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press,19 October 1895, p.8; 4 January 1896, p.5; 4 January 1896. p.5.

[39] Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press. 12 October 1895, p.7; 6 October 1894. p.8

[40] Bucks Herald, 4 May 1895, p.3; Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 4 May 1895, p.8; Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 1 June 1895, p.9.

[41] Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 12 November 1887. p.8; 26 November 1887, p.1; 16 April 1932, p.2.

[42] Buckingham Express, 7 April 1888, p.5; Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 7 December 1901, p.5; Buckingham Express, 18 May 1889, p.5; Buckingham Express, 5 November 1892, p.5; Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 1 September 1894, p.8; Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 21 April 1900 p.5; Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 17 August 1901, p.8.

[43] Civil registration death index; national probate index.

[44] Wellington Journal, 2 November 1901, p.6; Buckingham Express, 9 November 1901, p.4.

[45] Buckingham Express, 7 December 1901, p.5.

[46] Buckingham Express, 22 February 1902, p.8.

[47] Cambridge University Alumni, 1261-1900.

[48] Buckingham Express, 7 December 1901, p.5.Banbury Guardian, 28 April 1904, p.8.

[49] Banbury Beacon, 31 May 1902, p.8; Banbury Guardian, 5 June 1902, p.4; Banbury Guardian, 12 June 1902, p.8; Banbury Advertiser, 12 June 1902, p.5; Banbury Advertiser, 17 July 1902, p.5; Banbury Guardian, 24 July 1902, p.8.

[50] Banbury Advertiser, 18 June 1903, p.8; Banbury Advertiser, 25 June 1903, p.6; Banbury Advertiser, 25 June 1903, p.5; Banbury Advertiser, 12 November 1903, p.8.

[51] Banbury Advertiser, 27 March 1902, p.8; Banbury Beacon, 20 June 1903, p.8; Banbury Guardian, 28 April 1904, p.8.

[52] Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, 22 August 1902, p. 11.

[53] Buckingham Express, 13 June 1903, p.5.

[54] Lewisham Borough News, 28 April 1904, p.4; Bromley and West Kent Telegraph, 23 April 1904, p.8

Sevenoaks Chronicle and Kentish Advertiser, 16 December 1881, p.8.

[55] The will of Elizabeth Butler Hancock, dated 25 February 1897, proved in London on 9 June 1904. Two of her children predeceased her: Herbert James Beck Hancock in 1891 and Mary Ann Elizabeth Harston in 1895.

[56] East Anglican Daily Times, 28 September 1904, p.5; Cambridge University Alumni, 1261-1900.

[57] Norwich Argus, 13 May 1905, p.6; 20 January 1906, p.7.

[58] Devizes and Wilts Advertiser, 24 October 1907, p.2.

[59] Luton Times and Advertiser, 6 October 1905, p.8.

[60] Bedfordshire Mercury, 3 July 1908, p.7; 14 August 1908, p.6.

[61] Western Chronicle 18 June 1909 p. 6; Chard and Ilminster News 19 June 1909 p. 3.

[62] Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser 28 July 1909 p. 1.

[63] Western Chronicle, 11 February 1910, p.6; Western Gazette, 25 March 1910, p.3.

[64] Western Gazette, 25 March 1910, p.3; Western Chronicle, 1 April 1910, p.6.

[65] Western Chronicle, 15 April 1910, p.5.

[66] Burton Chronicle, 5 October 1911, p.4.

[67] Peterborough Standard, 2 March 1912, p.7; Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1908, p. 1368;

[68] Northampton Mercury, 1 March 1912, p.5; Peterborough Advertiser, 2 March 1912, p.2; Northampton Herald, 16 August 1912, p.9.

[69] Northampton Herald, 23 February 1912, p.10.

[70] Crockford’s Clerical Directory, 1932, p.1040.

[71] Midland Mail, 28 April 1900, p.3.

[72] Midland Mail, 28 April 1900, p.3.

[73] Kelly’s Directory of Leicestershire & Rutland, 1916, pp.673-74.

[74] Grantham Journal, 11 September 1915, p.2; 11 August 1917, p.2.

[75] Grantham Journal, 23 October 1920, p.8; Stamford Mercury, 20 May 1921, p.6.

[76] Stamford Mercury, 20 May 1921, p.6; Hunts County News, 6 May 1921, p.4; National Probate Calendar (Mildred Brander Wilson).

[77] Leeds Mercury, 24 September 1927, p.1; Nottingham Journal, 29 May 1928, p.11.

[78] National probate register.